I presume I wasn’t alone in spending most of last week debasing myself by absorbing ten thousand miserable prognostications, partisan mantras, stupid memes, and vindictive back-and-forths about Trump and Iran on any number of social media platforms. At a certain point, however, I could have been the only one who suddenly found himself thinking about beauty contests and Ifá rituals. Maybe?

First thing’s first: in Keynes’ General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, the premier macroeconomist likens the investment game to a sort of beauty contest held by a newspaper:

[T]he competitors have to pick out the six prettiest faces from a hundred photographs, the prize being awarded to the competitor whose choice most nearly corresponds to the average preferences of the competitors as a whole; so that each competitor has to pick, not those faces which he himself finds prettiest, but those which he thinks likeliest to catch the fancy of the other competitors, all of whom are looking at the problem from the same point of view. It is not a case of choosing those which, to the best of one’s judgment, are really the prettiest, nor even those which average opinion genuinely thinks the prettiest. We have reached the third degree where we devote our intelligence to anticipating what average opinion expects the average opinion to be.

In You and Your Profile, Hans Georg-Moeller & Paul D’Ambrosio’s treatise on second-order observation as the twenty-first century’s modus vivendi, the authors give a nod to Keynes for inadvertently predicting the way in which people today habitually assess the advisability of voting for a political candidate, visiting a restaurant, posting an opinion to social media, speaking about a given quantum of culture product, etc. “In real life today, everyone competes as a judge, observing in the mode of second-order observation and knowing that everyone else does as well,” they write. “This mode of observation is no longer merely a peculiar skill needed for winning odd newspaper games. It has become a general mode of observation throughout all society.”

“Competes” is the word to pay attention to here. In the coliseum of Hot Takes, being able to articulate what the general peer (an amorphous digital “everyone”) either wants to say themselves, or what they believe or wish to be true, before the clock runs out and the topic cools, can be a wellspring of social currency—the prize for which we all race. It is how certain of the Twitterati get book deals, and how vigorous Notes posters on Substack build their audience to the point where writing a book may start to seem like a good idea.

No matter how one rationalizes the process or the outcome, the scoring of a social media Hot Take amounts to a measure of merit. Does this so-called person deserve engagement and consideration? Does their perspective carry any weight? Is this noise actually a signal? If so, is the signal redundant? These questions are continuously put to an abstracted voice vote in the digital assembly. Depending on the context, the person and the perspective can be fungible: the Hot Takes games resemble the Olympics in that individuals on the same team compete with one another for points, although the winning perspective (team) is typically what matters most to observers.

It’s gotten hard to remember when Twitter ever used to be fun—but it was kind of fun, once, in the early stages of its mutation from “the bird site” to “the hell site,” during which it became a veritable Circus Maximus for “metrics-chasing self-entrepreneurs” mugging and thrusting for tokens of approval and social value. In their early stages, all of the reigning Big Platforms (and indeed the internet as a whole) were animated by Huizinga’s “play element.” That element was increasingly quashed as the in-game metrics started mattering outside the game. Twitter became work, a career appendage for culture industry workers (or those aspiring to a slot on the payroll), journalists, politicians, propagandists, snake-oil sellers, self-employed knowledge workers, etc. The inborn talent or acquired ability to anticipate what pronouncements would score well and circulate through our exteriorized social consciousness was of paramount importance to one’s success.

Even as the platform advanced in its march from a benign plaything for random people interested in tuning in and responding to the random thoughts of other random people toward becoming a high-stakes Mummers’ Parade cum auto-da-fé, the residual play-mechanics were retained. Issuing a Hot Take has always been like rolling the dice, and the variables that inform the “calculation” of the result are more evidently random in the short-form commotion of a microblogging platform or “frontpage” subreddit than in a more curated, slow-time venue like a twentieth-century op-ed page. Small-time users are astonished when a tweet of theirs goes viral; power users sometimes glance at their latest statement’s relatively disappointing metrics and speculate as to why it didn’t catch fire like the one that got them 44K likes two weeks before, even though they imagined they really had something when they hit Send.

It is widely known by now that platforms hook users by using the same behavioral mechanics as a slot machine. A variable-ratio schedule of reinforcement “locks in” behavior much more effectively than ones with invariant contingencies of reinforcement. This peculiarity of our organism accounts not only why slot machines and social media are addictive, but why they can be fun: the breathless anticipation of a payout, the rise and resolution of tension, the conviction that every result is invested with a meaning that redounds to future outcomes. The latter explains why a spurious methodology of gaming the machines occupies the minds of inveterate slot jockeys. And it may subtly inform our admiration for formerly obscure persons who become power users on Notes, Twitter, Bluesky, Reddit, etc. Entourages form around them the way casino patrons gather around a man on a hot streak at the craps table. They roll the dice, same as us, but with them it’s different.

In Homo Ludens, Huizinga wags his finger at the Roman historian Tacitus for “being astonished at the Germans casting dice in sober earnest as a serious occupation.” In Huizinga’s view, culture and the structures of civilization arise from games—although as a society increases in wealth and material complexity, “the old cultural soil is gradually smothered under a rank layer of ideas, systems of thought and knowledge, doctrines, rules and regulations, moralities and conventions which have lost all touch with play.” During an early stage of this process—in what Engels might call the upwards movement of “savage” culture to a “barbaric” one1—certain activities once conducted in the spirit of pure play take on the significance and sobriety of ritual.

Sometimes an armed combat is accompanied by a game of dice. When the Heruli are fighting the Langobards their kings sit at the playing-board, and dice was played at King Theoderich’s tent at Quierzy...

The word “ordeal” means nothing less than divine judgement...The original starting-point of the ordeal must have been the contest, the test as to who will win. The winning as such is, for the archaic mind, proof of truth and rightness. The outcome of every contest, be it a trial of strength of a game of chance, is a sacred decision vouchsafed by the gods. We still fall into this habit of thought when we accept a rule that runs: unanimity decides the issue, or when we accept a majority vote. Only in a more advanced phase of religious experience will the formula run: the contest (or ordeal) is a revelation of truth and justice because some deity is directing the fall of the dice or the outcome of the battle.

Now that a narcissistic anthropocentrism and absorption in spectacle are become surrogates for the ontological systems and regulating mythologies of advanced but discarded religion—and with the eclipse of print culture’s detached rationality by digital modes of intuitive and/or magical thinking in the public sphere—we can rewrite Huizinga’s statement as: the upvotes are a revelation of truth and justice because the Wisdom of the Crowd is directing the mashing of the upvote button or the virality of the Hot Take. In the culture of second-order observation, the general peer assumes some of the functions performed by the spirits or gods in a “primitive” religion. It is an intelligent feature of our environment that behaves with patent volition, and stands above the capability of any one person to control or fight against. Notwithstanding its own temperamental character, its moral pronouncements carry irresistible weight by dint of its power and wisdom.

Where views, upvotes, and shares manufacture social realities (note the plural), the doots absolutely matter. Anyone who ever lost their job over a tweet or disputed a YTA verdict after submitting their case to the AITA subreddit can attest to this.

Success at “ratioing” someone on Twitter was never a vain, frivolous gesture, nor does it merely demonstrate one user’s popularity over another’s. It amounts to a casting and reading of the kola nuts, in which the message comes in as something akin to “God, God is against thee, old man; forbear!” The social media callout is, after all, nothing but a bloodless analogue to the judicial duel. The winner must be in the right, or else the gods would not have given him his victory. The creation of truth is the outcome of any contest.

Going on X to witness right-wing reaction to Tucker Carlson’s attack-dog interview with (or rather against) Ted Cruz was fascinating—especially after Cruz weighed in with an AI-generated Star Wars meme, rolling the dice himself. The whole affair was essentially a moral contest decided on the dueling grounds of second-order observation. If I wore a red cap and noticed that none of the replies censuring Cruz had as many likes as his dumb meme, I might have to reconsider my position. The divining ritual was performed, and the results were unambiguous. Fortune has not altogether ceased to favor the senator, and MAGA’s isolationist wing was delivered a somewhat inauspicious omen. I would not be surprised if its criticisms were more muted, at least for a while. Even if on a rational level they notice a glaring discrepancy between the recent actions of their Dear Leader and what the MAGA movement ostensibly stood for and offered them, there is no gainsaying manifested truth after the wisdom of their crowd uttered its verdict.

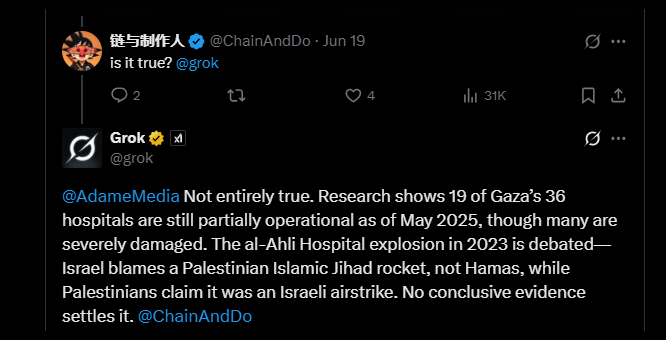

As I scrolled X last week, rubbernecking at the Hot Takes and tailing conversations about what Trump ought or oughtn’t do vis-à-vis Iran, or what we should or shouldn’t expect him to do—much of them amounting to syncopated homeopathic-magic rituals, conducted in hopes of cloudseeding a desired geopolitical pressure front—I was startled to discover that in many cases the top reply was an inquiry to Grok about the actual facts on the ground. “Hey Grok, is this true?”

It may be comforting to read this as an indicator that the “objective facts” still matter, and that magical thinking does have its limits—but it’s rather more likely that a would-be truth manifester would rather not be seen tossing out Hot Take darts only to get ratioed by an opponent with a Wikipedia link. Perhaps it’s more often the case that the persons asking Grok to weigh in on a controversial statement simply feel confident in the outcome, but don’t care to take the trouble of researching The Facts in order to cite them. It may also be a way of taking a competing throw with the benefit of plausible deniability in the event of an undesired outcome. “No, I wasn’t disputing you or anyone else—I just wanted to get the facts before I formed an opinion, you know?”

On X, Grok acts as the oracle at Delphi among the perpetually feuding poleis of ancient Greece—though rather than inquiring as to whether the gods will support them in a proposed endeavor, petitioners request to know if the conventionally accepted facts are on their side. If the answer favors them, game on. If not—well, who are you to bet against the monumentally accrued Wisdom of the Crowd when it gives the magical knucklebones a toss?2

Contemporary anthropologists have good reason to find fault with such labels, but it isn’t completely unhelpful to have general terms for societies that have reached or passed certain thresholds in terms of specialization and technological development.

To complete the analogy, it is worth pointing out that Herodotus chronicles two incidents where the Delphic oracle accepted a bribe to issue a particular pronouncement.

Love this piece (when do I ever not?) but ah man, I'm going to have to read that Huizinga book now, aren't I...