Oh, why the hell not.

Does anyone remember the show Millennium? If yes, follow up question: are your recollections of Millennium more concrete than oh, that was the other Chris Carter show, the one nobody watched?

I only caught it once during its original run: season two’s “Somehow, Satan Got Behind Me,” authored by X-Files fan-favorite Darin Morgan. I’m at pains to think of a single stray episode of anything I saw as a teenager that left such a durable impression on me.1 It didn’t prime me to catch the next episode—I could tell it was an atypical one-off that didn’t represent the show as a whole—but it would have been what I thought of fondly whenever Millennium was mentioned in the years afterwards, if only anyone ever mentioned Millennium. The series was ignored during its run and forgotten after its cancellation. Buying the old DVDs or turning pirate are the only ways of watching it today.

After returning to Darin Morgan’s X-Files episodes during my recent binge, I watched “Somehow, Satan Got Behind Me” with my wife. It was as good as I remembered, and it made me curious to see what Millennium was actually about.

What Millennium is actually about kind of depends on which season we’re talking about. In any case, it is dreadfully underrated.2

The series begins with former FBI agent Frank Black relocating to Seattle with his wife and daughter, where they move into a picturesque yellow house in a beautiful, safe neighborhood. Scarcely have they settled in when Frank glances the newspaper, catches an article about a killer at large, and wastes no time getting himself involved in the investigation as a professional consultant. Even though he left the bureau, Frank can’t quit the game. His forensic expertise, spooky intuition, and understanding of serial killers’ psychodynamics are too valuable to remove from play, and Frank has an urgent and deeply personal need to protect the innocent from the ontological evil that interfaces with the world through ghastly lunatics.3

Even though the pilot was a tour-de-force, it’s not hard to see why viewers started tuning out before the first season was over. Millennium is unrelentingly dark and, like anything with Carter’s name on it, susceptible to hamfistedness. Week after week: serial killers, grisly murders, psychopathology, meditations on the nature of evil, no quips, no levity, and little tonal diversity—a train of variations on the themes of Thomas Harris novels and Seven with occasional intimations of the supernatural and apocalyptic. But as Ash said of the xenomorph in Alien, I admire first-season Millennium’s purity.4 For better and for worse, it makes no pretense of trying to compromise with a mass audience for whom plumbing the nether regions of the soul and glimpsing something obscene and alien ranks fairly low as a fun thing to do on a Friday night.

Season two is where the magic happens. Carter gave the cockpit over to X-Files alums Glen Morgan (Darin Morgan’s brother) and James Wong, who reportedly needed little pressure from the network to decide they ought to guide Millennium in a new direction. The supernatural and theological undertones of the first season become overtones—and yet, the narrative less often paints Evil as a malignant external force than as something fundamentally and even banally human. The cast members who weren’t pulling their weight are either minimized or fleshed out, and new faces appear to contribute some sorely-needed variety. A retcon transforms the Millennium Group from a consulting firm that works with law enforcement to a secret society akin to the Knights Templar. Frank lightens up—a little. The “serial killer of the week” outings are thinned out and dispersed, and the swivel towards the paranormal gives the writers more leeway to characterize one-off antagonists in terms other than “look how fucked up this episode’s bloodthirsty maniac is.” It’s still a dark show, but it gets weird and it sometimes even gets fun.

Observing that The X-Files and Millennium are both superlatively Nineties in their sensibilities and perspectives, Darren Mooney of the M0vie Blog suggests that the shows’ outlooks differ in terms of how they relate to globalization and the United States’ victory over the USSR in the Cold War: “It could be argued that The X-Files was a story concerned with the legacy of the choices that had been made to ensure that victory; the voices of conscience calling out from history like disembodied ghosts. In contrast, Millennium seemed to wonder what lay ahead.”

A more superficial analysis would find that Millennium is sort of like a version of The X-Files whose mythology extends its taproot into the chthonic and apocalyptic lore of Christianity instead of alien abduction legends—and it cannot be said that angels, demons, the Seven Seals, and “1999 → 666?!?” didn’t belong to the mid-to-late 1990s zeitgeist in the United States. Superstitious concerns frequently infiltrated more secular anxieties about the end of the century (and indeed the end of the millennium). 2000 was just a number, sure, but a society that relies so much its calendar to orient and collocate its activities can’t but perceive an ineffable significance in such a salient turning of the page. Books and chatter about the Antichrist and the New World Order circulated amongst believers. Nostradamus and the Book of Revelation appeared on tabloid covers and on trashy TV shows. As the millennium approached, even not-altogether religious Americans discovered a morbid allure in mapping intimations of its importance over prophecy and Christian eschatology. It was part of the cultural ambiance, and Millennium got a lot of thematic and dramatic mileage out its End of Days subtext.

But this contributes to making Millennium feel even more like an expired product of its time than The X-Files. The real-life countdown to 12:00 AM 1 January 2000 and background whispers of an impending Event that invested Millennium with an air of immediacy are long past. Moreover, like Mulder’s devotion to conspiracy theories, the stuff of the Millennium Group’s doomsday prophecies has since become solidly right-coded and crank-coded. I don’t doubt that a youngster shown the X-Files’ pilot for the first time would compare Mulder to any number of unsavory internet paranoiacs, and might also catch the vague scent of kooky, QAnon-ish evangelism from Millennium’s eschatological ominousness and myriad biblical references. Fewer people are inclined to suspend their disbelief (or mislike) of this stuff today than thirty years ago.

Though the Antichrist was a no-show, our entry into the new millennium was in fact occasioned by a transformation of the world on par with the “Earth Changes” prophesied by New Agers and psychics throughout the twentieth-century—and the second-season episode of Millennium titled “The Mikado” addresses it. Its plot, in brief: the Zodiac Killer is back, and now he’s on the Information Superhighway.

Okay, it’s not really the Zodiac Killer: here he’s called “Avatar,” and he went on his rampage in the 1980s, not the 1960s. But anyone familiar with the Zodiac Killer would recognize Avatar’s penchants for cryptographic messages, the Gilbert & Sullivan musical The Mikado, and murdering couples.

“The Mikado” begins with a pair of teenage boys looking for internet porn in lieu of doing homework. They’re joined by a third, who tells them an acquaintance of his passed on a promising website he found while “lurking in a chat room for perverts.” Punching an IP address into the URL field, they’re taken to a simple homepage whose banner reads “The Mystery Room.”

At the center of the page is a still photo of a half-naked woman tied to a chair in a dim room. The numbers 37122 are painted on the wall behind her. A hits counter sits in the screen’s lower right-hand corner. It’s sort of like a crude livestream: at regular several-second intervals, the image refreshes. The boys speculate that it’s some kind of bondage performance. The hits counter rolls up to 37122, matching the number on the wall. A man in a black hood appears. In following frame, he’s seen slashing the woman’s throat with a knife. When the image refreshes, the man is gone.

The boys hit Print Screen before the site disappears. Although police departments across the county receive phone calls from shaken web users claiming to have witnessed a murder, the printout becomes the only evidence that a crime was committed. The Millennium Group gets involved. When Frank asks which law enforcement agency has been tasked with the investigation, his associate Peter Watts answers: none of them.

“No law enforcement agency can claim jurisdiction until we can find out where this happened,” Peter Watts says. “The law just hasn't kept up with the technology.”

“The web has become his world,” Frank’s spooky intuition tells him about the killer. “He showed her off on the internet. He killed her on the internet. I believe that’s where he first found her. He stalked her—then made contact in cyberspace before abducting her in real life.”

After identifying the victim, Frank & co. hack into her ISP account and find that she frequented newsgroups such as “alt.xxx.bondage,” “alt.xxx.boys,” “alt.xxx.erotica,” and so on. The suspect they identify after examining the prurient contents of her inbox is shortly exonerated—on account of being found dead, stuffed inside a shed with the victim.

The killer seizes another woman and displays her on a new website at a new IP address. The Millennium Group’s tech guy Roedicker tries to locate the phone line the killer is using to upload his pictures to his site—which I’m pretty sure can’t be done (please correct me if I’m wrong), but makes for an exciting Hollywood Hacking sequence.

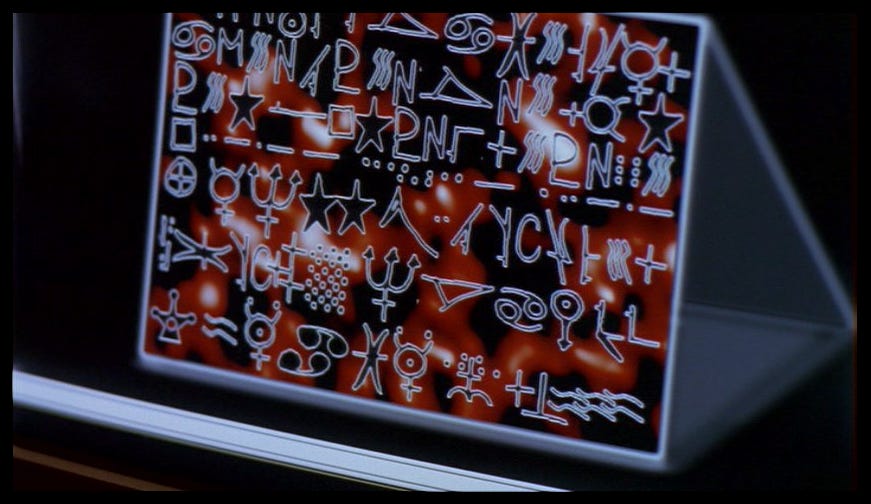

“That’s impossible!” Roedecker exclaims in astonishment as he watches the trace pinballing across multiple servers in multiple cities all over the world. “No one can do this!” The murderer is just too good at the internet to be foiled by a mere techie. Moments later, the refreshed image displaces the still of the victim-to-be with a cryptographic message, cementing Frank’s suspicion that the man they’re dealing with is the mysterious Avatar killer, returned from a twelve-year hiatus.

To make a long story short: at the episode’s climax, Frank’s weird sixth sense leads him to Avatar’s lair. He rescues the killer’s next victim, but Avatar escapes, leaving no trail behind him. Nevertheless, Frank is confident that they have nothing to worry about in the short term: Avatar, whoever (or whatever) he is, has finished playing with his new toy. He won’t reappear—“not in this form, not in this medium,” Frank tells Peter Watts.

“But when he finds that next thing, that next weakness—that’s when he’ll be there again.”

In the (admittedly murky) context of Millennium, Avatar is to be considered less as a human being and more as an instrument or instantiation of Evil itself, recapitulating the first primeval occasion of a human being employing fire for torture and murder. Every technology creates a theretofore nonexistent vulnerability, a new vector though which people can wreak misery upon each other. Before the invention of agriculture, nobody ever suffered from malnutrition or starvation after raiders set fire to their crops. In the Histories, Herodotus matter-of-factly calls the invention of iron implements “a bad thing for mankind,” and doubtlessly had weaponry in mind. The mere possibility of sectarian violence between factions with different interpretations of a religious text requires that texts exist in the world. “The Mikado” is an extreme dramatization of the historical process by which a technology embraced for its beneficial applications discloses its inimical aspect, its dark reverse.

When “The Mikado” aired in early 1998, it wasn’t altogether difficult to convince network television audiences that the web had a sketchy and dangerous side. Right up until the murder, the episode’s first scene could have been from a VHS tape distributed by a national church group, cautioning parents about what happens when teens have unsupervised internet access. (Porn.) Less than a quarter of American households had a computer with internet access at that point, and cyberspace was still anonymous, decentralized, and unmapped—an obscure continent with a culture foreign to most.

“Some people feel liberated from their normal self when they adopt an internet persona,” techie Roedecker explains to his middle-aged companions. “In the anonymity of cyberspace, people are free to experiment. Online I’ve changed my name, my appearance, sexual orientation—even gender.”

Not everyone watching “The Mikado” would have nodded in approval. To many, cyberspace looked like a nest of deviants and scammers eager to use the medium’s abstractedness to indulge their perversions and/or take advantage of the credulous. Conventional wisdom held that one should be extremely cautious about submitting a credit card number or sharing personal information anywhere online. Parents were advised that a child with an internet connection was liable to get sucked into a virtual world of solicitous pedophiles.

“The Mikado” does a fine job playing to what its audience already knew and worried about with regard to the early internet: the nascent state of the technical and legal tools for dealing with cybercrime, the rampant proliferation of XXX websites and chat rooms, and the dangers of opening up to totally anonymous people whose true identities and intentions were anyone’s guess. But in thinking out Avatar’s MO—setting up a website with a hits counter and executing his captive when the hits exceed a specified value—the Millennium team was incredibly, frightfully ahead of the curve.

From a conversation between the investigators:

ROEDECKER: The site’s been getting about four thousand hits per hour—that gives us maybe twenty-one hours.

FRANK: Four thousand people visit this site just because a girl might be killed…

ROEDECKER: Well, there’s a lot of repeat business—and most of them just hope that she’ll take off her clothes.

WATTS: Yeah, but some of them know what’s going to happen. They saw or heard about it on the previous site. Their actions now practically make them accessories to the crime.

From a legal perspective, those dozens or hundred of anonymous and untraceable degenerates who knew what was happening were accessories to the murders—but the kids who navigated to The Mystery Room out of curiosity also share some responsibility for bumping up the hits counter and summoning Avatar.

Not long after “The Mikado” aired, people were having similar conversations about Napster and its user base. Copying a CD for a friend now and then? Technically illegal—but harmless. Using P2P software to share the contents of that same CD with anyone else who’s got a computer and an internet connection? Catastrophic for the music industry, demoralizing for artists who hoped to maintain control over their work, and effectively impossible to halt. Sure, the record companies could (and did) pursue legal action against Napster, Kazaa, and LimeWire, but their courtroom victories amounted to so many rearguard actions. P2P applications facilitated what could be called a years-long mass looting campaign involving too many millions of individual users than could be chased down and served papers, and the industry finally had no recourse but to cut its losses and reconsider its distribution strategy. Too many people had gotten too accustomed to filesharing to ever spend their money in a record store again.

In a very basic sense, every economic and social disruption we can ascribe to the digital revolution boils down to: “some millions of people started doing [X].” The same can be said of any other technological paradigm shift, from the agricultural to the automotive revolutions. What “The Mikado” dramatizes—even mythologizes—is the switch point where a quantitative increase crosses the threshold of qualitative change.

During the aughts, tech enthusiasts extolled the Wisdom of Crowds. As the internet became less compartmentalized in public life and more consolidated around the major sites and platforms, the Psychopathy of Crowds was brought into increasingly sharp relief. Revenge porn, online pile-ons and flash crusades, disastrous message-board manhunts, the propagation of social contagions and outgroup hatred through digital networks—none would be of much consequence, and few even would be possible, unless there existed a pullulating mass of strangers independently clicking, viewing, typing, and sending, all physically isolated from each other and from the persons whom they are mediately acting upon.

The fact that the 1990s were hung up on cyberspatial Stranger Danger and the moral hazards of free XXX sites makes clear, in retrospect, that the internet’s critics and advocates alike lacked the imagination to detect its real potential for nastiness. What it awaited wasn’t smartphones or the big platforms’ social validation feedback loops per se, but for all of us to follow after Avatar—for the web to become our world, too.

Synopsis: in the wee hours of the morning, four old men sit down together at a table in an otherwise empty Dunkin Donuts Donut Hole. The four old men are actually demons. The demons talk shop for forty minutes.

This is as good a place as any to mention that the screencaps here are from the Millennium fansite This Is Who We Are, the first version of which was launched way back in 2001.

The first two seasons are, anyhow. I can’t comment on the third and final season because I haven’t seen it (I’m still recovering from the season two finale), and it doesn’t come highly recommended.

First-season Frank Black is pretty much an older, better-fortified, gravelly-voiced Will Graham. Here I will admit that I haven’t seen the 2002 film adaptation of Red Dragon and I’ve never watched the 2010s Hannibal series—but Manhunter is one of my all-time favorite movies. Like Millennium, it’s tragically overlooked, and I maintain that Brian Cox’s more grounded and less movie-monster version of Hannibal Lector is more disturbing than Hopkins’.

(Postscript: this got me curious to see how the Red Dragon film handles the “Will Graham figures it out!!” scene, which Manhunter executes with such magnificent 1980s élan. I cannot tell you how disappointed I was.)

I also admire its opening credits sequence, for it is the apotheosis of the Pretentiously Artsy Nineties Music Video aesthetic.

I could resist replying to the X-Files but you just had to get into Millennium didn't you?

When I was about 16 or in highschool I entered my evangelical Christian phase (yes, phase, thank God) and you better believe this show hit like a freight train for me. It was perfect timing. Your breakdown of its elements is spot on. This was a time when the internet was the place you went to do the absolutely insane stuff you'd never want to do in real life because, hey, on the web nobody knows who you are and can never find you, right?? That was basically true back in the day when the only people who understood this stuff were a handful of basement dwellers. This made the internet feel "vast and infinite".

Fast forward 15 years later and it's the EXACT OPPOSITE. The internet is now a tightly knit fisherman's net that remembers every single key stroke you log, forever, and is full of people ready and waiting to hunt you down in a moment's notice. Now I save my off the wall activities for real life, where, as long as nobody's recording, there's less accountability and nobody remembers anything.

It was too bad they ended the show the way they did. I always figured the perfect way to end it would have been a special episode airing at 11PM, December 31, 1999, ending just as the ball dropped in Rockefeller, written in such a way as to tie up the series in a satisfying way but also leave it open enough to match the fervor surrounding the world's obsession with the possibilities in the new millennium.

But that would have been WAY too hardcore. The only man with the grit and genius to pull that off already had his own series he was waiting to revive (RIP David).

P.S.

With Lynch's passing, have you thought about writing anything on him? I'm way too lazy to check your old stuff to see if you're a fan (also my memory sucks) but he seems like someone who's work you'd be into.

A Big fan of the series. Got to know it around 2008-9 through reruns in south american tv. After rewatching it last year i discovered most of My clearest memories were from The Mikado, a truly amazing piece of tv.

Would also like to hear your insight in "Midnight of the Century", "The Curse of Frank Black" and "José Chung's Doomsday defense"