Ever have a couple of weeks where you try to write, but none of what you’re producing gels into anything usable? I’m having a couple of weeks like that.

So today I’m saying the hell with it and reprinting a back issue with a few superficial tweaks. This one’s from 2020.

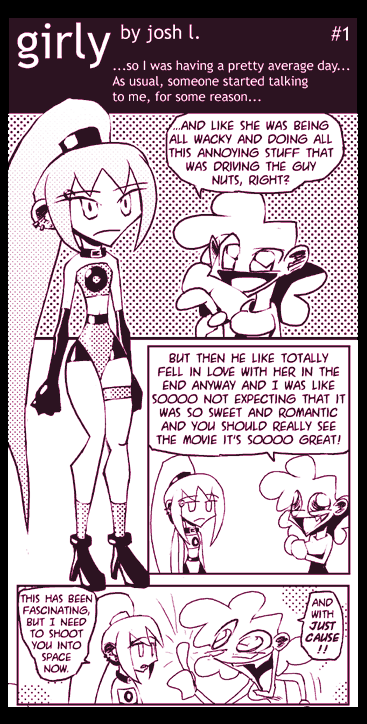

By whatever authority I have as a retired webcomic creator, I’d bracket the period from 2000–2007 as the golden age of the online comic strip.1 Not that we are or have ever been in danger of running out of well-written and visually captivating pictorial narratives to read in our browser windows, nor have digital comics declined in quality. To the contrary, today’s strips evince more technical proficiency and polish than the ones I followed in the early aughts, and which inspired me to try my hand at making one myself.2 But the glory days of the webcomic scene are nevertheless long past.

I won’t embarrass myself by trying to polish the infinitesimal legacy of my own contribution, but I do take some pride in having participated in what could fairly (if immodestly) be called a subcultural movement. The sphere of webcomics, with its DIY ethos, amicable social networks, and the kind of ingenuous passion not to be found outside of amateurdom, was for adolescents like me what the Jersey ska punk scene was to my more gregarious friends.

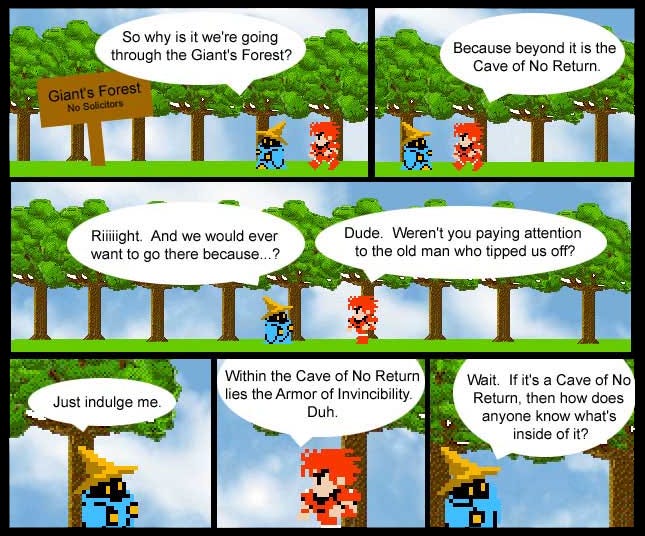

At the beginning, nobody began putting together comic strips and slapping them up on the internet as part of a plan to pay off their student loans. Money and fame weren’t the goal. Many of the early scene’s biggest names—including ones who remain active to this day and have blueticked Twitter accounts—started out making and sharing their comic strips purely for amusement. For the first year or so of its run, Zach Weiner’s Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal was a series of scanned pencil drawings he produced in class in lieu of taking notes.3 The first pages of Brian Clevinger’s 8-Bit Theater certainly don’t read like the work of someone who approached his web presence as though it were an audition for a Marvel Comics gig. David Rees assembled the first Get Your War On strips as a means of sorting through and screaming out his thoughts about the Bush Administration’s ghastly, shambolic crusade against “terror,” and even when it became a monthly feature in Rolling Stone, Rees leased no space to advertisers on his website, maintained an irregular update schedule, and permanently retired the strip when Bush vacated the White House.

By recent standards, even the brightest stars of early-aughts webcomics shone somewhat dim. In 2006, Penny Arcade (which owed its status as the big kahuna of online comics to having been around since dial-up modems) was getting two million views per day—which is roughly twenty percent of the daily traffic to PewDiePie’s YouTube channel. Far fewer people were aware of Fred Gallagher’s Megatokyo circa 2000–2005 than saw KC Green's epochal “this is fine” strip-turned-meme in the second half of the 2010s. Moderately popular comics like Nothing Nice to Say and Chugworth Academy had paperback collections on sale at Barnes and Noble, but neither they nor their creators ever reached the level of visibility enjoyed by even the B-listers of today’s influencer caste.4

It must be emphasized that before the mid-early-aughts, there were no tried and tested means of converting page views into revenue. They had to be invented. Before long, artists and writers realized they could quit their day jobs by selling ad space and T-shirts, finding publishers for printed collections, and soliciting donations (sometimes offering “cheesecake” pinups as donor gifts, skeevily prefiguring OnlyFans). In doing so, they were professionalizing what had begun as a just-for-fun endeavor, and a gold rush ensued. Hierarchies crystallized. Enterprising observers founded webcomics listings that offered exposure in exchange for money or traffic to their ad-smattered pages. Others wrote blog posts instructing artists in how to get noticed, insisting upon frenetic update schedules and targeted content, outlining networking strategies, and recommending cross-promotions with one’s other business ventures.

The evolution of the webcomic through the aughts may be correlated with that of the blog, whose development and coming of age were in many ways analogous to its own. People involved in the early-aughts webcomics scene who happened to read Silicon Valley archskeptic Nick Carr’s 2008 eulogy to the blogosphere may have found parts of his postmortem dismally familiar:

That vast, free-wheeling, and surprisingly intimate forum where individual writers shared their observations, thoughts, and arguments outside the bounds of the traditional media is gone. Almost all of the popular blogs today are commercial ventures with teams of writers, aggressive ad-sales operations, bloated sites, and strategies of self-linking. Some are good, some are boring, but to argue that they’re part of a "blogosphere" that is distinguishable from the "mainstream media" seems more and more like an act of nostalgia, if not self-delusion.

The buzz has left blogging...and moved, at least for the time being, to Facebook and Twitter.

I was a latecomer to blogging, launching Rough Type in the spring of 2005. But even then, the feel of blogging was completely different than it is today. The top blogs were still largely written by individuals. They were quirky and informal. Such blogs still exist (and long may they thrive!), but...they’ve been pushed to the periphery.

The trends of careerism, overcrowding, competition, and immitigable stratification doomed the old blogosphere to elanguescence and sapped the webcomics scene of much of its early energy. However, the changes wrought upon each by the renovation of The Information Superhighway into Web 2.0 were not identical. The webcomic artist never found herself trying to keep pace and fight for attention with the visual-narrative equivalent of Gawker or the Huffington Post—but by the same token, search-engine optimized content mills had little interest in putting her on the payroll. And the blogger, to the best of my knowledge, was never inveigled into paying a monthly fee to a scammy “Top Blogs” index to put his banner or link button into rotation the way the frustrated and unnoticed webcomic artist was, nor was he as likely to have been tempted to produce erotic content for attention and commissions.5 In any case, by 2010 it was abundantly clear that the wave on which amateur comickers and chroniclers had rode in at the start of the decade had crashed and receded.

Much of what made the early-aughts internet’s culture and landscape so interesting were those elements that had rolled over from the modular nineties, when most commercial websites were basically pamphlets and catalogues in hypertext, content aggregators were practically nonexistent, and the upvote button was still a twinkle in Justin Rosenstein’s eye. If you were to open your browser window in 1997 and search for "x files" on WebCrawler or Yahoo, most of the results would be homebrewed personal pages. After clicking on a link and browsing an enthusiast’s plot summaries and mythology theories, you might arrive at a links section and click around to see what other topics and people your host fancies. You might find an X-Files webring panel at the footer and go on to find out how the next webmaster in the chain brings his or her own sensibilities to bear on the same material.

Fanpages like these were often subsections of somebody’s personal website. After reading about Mulder and Scully, you could usually follow a link back to the homepage and learn more about your host.

Dwelling on the typically crude designs of the old personal sites that proliferated around the turn of the century (to this day, GeoCities remains synonymous with distracting gewgaws, unreadable text, and ugly wallpaper) is to miss the forest for the trees and overlook much of what made the internet’s “wild west” iteration so much fun to explore. Here were hundreds and thousands of enthusiastic dabblers who went about constructing their web presences not as résumés, networking instruments, or business investments, but like sandcastles, cheerily piling them up and inviting people to come over and look at what they’d made. True, many of them had only a passing knowledge of HTML and could have benefited from a short course in color and composition theory, and a staggering proportion were solely committed to celebrating mass media ephemera. But these hypertext collages, made under no compulsion and freely offered to the world, don’t represent a "primitive phase" of online content generation so much as a brief flowering of folk art. A bastard kind of folk art, sure, but an active strain of culture nonetheless.

There were no winners or losers here. The hits counter at the bottom of our webmaster’s X-Files page might have registered less traffic than the one displayed on the more polished and comprehensive site preceding his on the webring, but what did that matter? It was all in fun. Nothing was actually at stake.

By the end of the aughts, this attitude was considerably more difficult to maintain.

The centripetal tendencies of the maturing internet, and the discovery that views could be alchemized into revenue through targeted advertising and data collection, created clear winners and losers. The upper-echelon webcomic artists paying off their mortgages by leasing ad space and selling merchandise, and the entrepreneurs who founded profitable media companies that factory-farmed bloglike content were not losers by any metric, but in the big picture, they were runners-up. The real winners were the emerging social media giants: platforms that devised the revolutionary business model of recruiting users as an army of unpaid laborers continuously manufacturing content while simultaneously consuming other users’ content, free of charge, along with precision-targeted and paid-for marketing material.

The major platforms’ clearing of the neighborhood was accomplished between the mid-aughts and the mid-twenty-tens. At first, the artist or writer would take to Facebook, Twitter, and/or possibly Tumblr to promote their work and link to their offsite personal pages. Over time, they discovered that the platforms (and their massive, built-in audiences) favored content that wasn’t hosted offsite. The webcomic creator who’d worked like hell to amass a sufficiently large and reliable audience to earn a modest income through banner and sidebar ads found those revenues shrinking as his fans shared his latest strips on Twitter and Facebook without actually linking to his page. The Wordpress blogger began to notice that her tweet rants were getting more engagement than the links to her longform pieces. By and by, the personal comics page, illustration gallery, or blog became pointless (except as a stiff, perfunctory “portfolio”) unless its owner was already established and recognized. It’s simply more expedient now for the creator to host her material exclusively on Instagram, YouTube, Tumblr, etc., and include a Patreon link in her bio blurb.

An immediately apparent consequence of the mass migration onto the giant platforms was the user’s sacrifice of control. The homepages of the nineties and early aughts looked janky, but they had flavor. They included nothing that their designers, amateurish though they might have been, didn’t make the deliberate choice of putting there. A common complaint of Facebook’s early detractors was that the new platform, unlike the earlier user-friendly substitutes to the personal site (Xanga, LiveJournal, etc.) didn’t allow users to modify their pages’ appearance or layout. This has since become so standardized across social media that nobody even thinks to gripe about it anymore.

A matter of greater concern were the parameters the social media giants imposed upon the content a user might wish to share. We’re all familiar with Twitter's character limit and its incentivization of histrionic, paranoid gibberish. Fandom, née Wikia—the personal fansite’s crowdsourced, for-profit replacement—welcomes (unpaid) contributions, but requires that its articles conform to the organization and house style established by Wikipedia. More subtly, Instagram and Facebook truncate post text with a "see more" tab after a certain number of line breaks, disincentivizing posts that run over that length. In the same manner, Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter discourage the posting (and thereby the creation) of images that deviate from the platform’s preferred aspect ratio. On Facebook and Twitter, a comic strip that must be clicked on and expanded to be viewed in full is liable to getting scrolled past. Permission to share links is granted, but grudgingly: the preview displays on those platforms cut off headlines and the excerpted text, and give the user little control over the thumbnail image. Getting the link to your blog, comics page, or whatever else to look good enough to compel someone to momentarily put the brakes on the forever scroll takes a bit of doing and know-how, and this is intentional. A platform that earns most of its revenue from sponsored content has an interest in dissuading its users from navigating away from its digital fief and from asking other users to do so.

Among the most noxious of these platforms’ locked-in features are the points system and the public scoreboard, which act as the vectors for some of the salient tech-related pathologies: Facebook and FOMO, Instagram and self-doubt, the mass-hypnotic atavism of Twitter, and so on. Having one’s performance graded and constantly seeing everyone else's rankings displayed within sight of one’s own can make social media overwhelming and humiliating, even for people who just want to share photos and thoughts with their circles of acquaintance. It’s not much better if you're “good” at it: prolific and popular Twitter users claim the platform makes them anxious, and it isn’t simply from absorbing brain-rotting invective like a shorebird soaking up an oil spill. They report the anxiety that precedes the submission of content and the disappointment that sometimes follows: Oh god is this a good idea what if it doesn’t perform well what if nobody cares? And: Oh god it’s been thirty minutes and still no likes what did I do what did I do wrong? I recently had coffee with a woman whose roommate, she tells me, is an "influencer-level" Instagram user, and apparently has a fitful, anxious relationship with the app.

For amateur creatives or aspiring professionals, using social media to “put themselves out there” can be miserable and degrading—but what alternative is there unless they’re already well-connected? The comic illustrator who wants to share her work with more people than just her coworkers and Tinder dates has little choice but to subject herself and her practice to the malignant Skinner box of social media, where she has before her at all times a numerical readout of how precisely many people gave a damn about her last contribution, how many people give a damn about her in general, and how her valuation compares to that of her former SVA classmates, her high school friends who went into different fields, and more successful artists. She knows that her cumulative record factors into the way other users prejudge her, and is aware that her popularity determines whether her profile and content will show up in other users’ algorithmically-generated feeds.

In such an environment, it’s easy to feel like the kid who drops a card into all his classmates’ Valentines Day boxes and receives none himself. What the hell am I doing wrong? What does it take?

Several of the amateur illustrators I follow on Twitter exhibit a cyclic pattern: over a period of two weeks to a month, they’ll post one or two drawings a day—which is fairly prolific for someone with a full-time job. Some will get a few likes, and maybe a retweet or two. Then one night they’ll tweet something like “I’m in a bad headspace I need some time away” and disappear for a while. When they return a week or two later, they’re in better spirits, but they usually take some time to get back into the groove. They’ll post some drawings and watch the Notifications icon light up a few times. Their tweets suggest they’re satisfied with their recent pieces; they ramp up their output over the next couple of weeks. Then they crack, announce they’re depressed and apologize to everyone, and vanish again. (This isn’t restricted to the illustrators in my feed; I see it among a few Twitch streamers as well.)

Perhaps my memory is unreliable, but I don’t recall this happening so frequently or so conspicuously on any of the old message boards and IRC channels I used to visit.

When an artist chooses social media as the venue for their work, there’s a good chance that the self-reinforcement of the creative process will lose its efficacy as a behavioral variable as the conditioned reinforcer of the Notifications icon acquires control. This is precisely what Instagram and Twitter are designed to do, and it’s the key to the variable-ratio reinforcement schedule on which their business models are founded. A small, irregular trickle of conditioned reinforcers (likes, shares, replies, new followers, etc.) is not only adequate to keep a habit locked in for a long time, it does so more effectively than a fixed-ratio reward schedule.6 Undoubtedly you’ve read elsewhere that this is the same behavioral hack that makes a gambler unable to tear herself away from a slot machine. It makes its epiphenomenal ingression as the goading supposition that this time might be different.

The comparison of Instagramming to slot jockeying is an apposite one, given the implication of a potential jackpot. Social media, like a Vegas casino, dangles the remote possibility of a life-changing, liberating payoff in front of visitors’ faces. You could go viral. You could become Internet Famous. You never know. The comic artist familiar with Kate Beaton and Allie Brosh knows that shares and retweets gave them careers. The writer trying to sell her first manuscript shortly becomes aware that literary agents are just as interested in her social media stature as they are in her novel’s plot or her skill as a prose stylist. The Instagrammer and YouTuber both know from the onset that surpassing a certain number of followers is the first step toward leveraging their influence to generate income.

And it’s hard to blame people for wanting to play the game. By all accounts, becoming a one-person content mill is exhausting— but so is ferrying people around the city as an Uber driver, steaming lattes at Starbucks, bussing tables at TGI Friday’s, getting yelled at by angry customers at a call center, and scuttling around an Amazon warehouse. Even if running oneself ragged working on illustration commissions and following through on promises to Patreon donors ultimately doesn’t generate much more income than a wage job, at least it would mean getting a little fucking recognition from someone.

The background of the present narrative, from GeoCities to TikTok, has been a world in which conditions for working people have grown worse for decades. Wages haven’t kept up with productivity increases. The workday has grown longer and the workplace more alienated. The hollowing out of the middle class and the trend of downward economic mobility has produced a generation of art-school and humanities graduates stocking supermarket shelves and signing up to be DoorDash drivers. Probably the competition and desperation for social media success through reptile-brained microblogging, memes masquerading as comic strips, lewd illustrations/selfies, etc. wouldn’t be so fierce today if people didn’t hate their goddamned jobs so goddamned much—and their stations in life might not be the source of so much ressentiment if their wages could buy them even the reasonable hope of homeownership, if the length of the workday or workweek were shorter, or if employers and the public were more inclined to treat working people with even a modicum of dignity.

The social complex that has made wage labor increasingly precarious and degrading since the mid-twentieth century is also responsible for the conditions that drove a cohort of withdrawn creatives online to find friends and express themselves. As nostalgic as we might be for the old internet, much of its contents were an indirect product of late-capitalist social atomization. One makes a Tinder profile today because meeting potential partners offline has become exceedingly difficult in the face of IRL social networks’ (churches, civic organizations, labor unions, clubs, bowling leagues, etc.) disintegration; in 2002, the reason one shared her drawings of Tenchi Muyo! characters on DeviantArt was that her classmates or coworkers (and who else was/is there, really?) weren’t interested—or perhaps because the people in her personal orbit mattered less to her than the idea of an “audience” inculcated in her by the mass media, celebrity culture, and a generally atomized way of life. In any case, fewer people would have gone to the internet to express themselves if more immediate social reinforcers operated more abundantly and effectively than electronically mediated rewards.

The early internet—webcomics, blogs, personal homepages, and all—was an uncoordinated group effort to escape from the social disconnection, competitive pressures, and hierarchical structures of the turn-of-the-century capitalist state by cultivating a breathing space in a newly formed interstice of its architecture. It has been difficult for me to come to terms with the fact that much of what the early “netizens” accomplished ultimately amounted to preparatory work for their colonizers. To have been involved in the webcomics scene when it was still exciting and relatively egalitarian was a joy, but the signification of the “.com” domain extension should have warned us what was in store. From the beginning, cyberspace was meant to become another facet of corporate-driven mass culture.

Many of us old enough to remember the world before wi-fi—when the web was a desktop retreat from the aggravations of school and work, the vicissitudes of social life, and the Serious narratives of the day—are still apt to express our astonishment at how much the internet has become like the “real” world. Over the last few years, I’ve often had occasion to wonder if an inflection point has been passed, and real life is starting to become less like the internet. The web has become so overheated, so populous, so relevant that offline pursuits and groups have become a source of respite.

I find myself coming back to this idea whenever I wander into a poetry reading, an open-mic night, an amateur theater performance, or a wee little concert somewhere in town. Some time ago I went with a friend to a local zine fest, and it was truly heartening to see people just sharing their stuff and casually yakking it up with attendees. And how few clout-chasers and crass self-promoters there were! There were plenty of people who’d come out hoping to sell books and stickers, sure, and obviously everyone with a table intended to do at least a little networking—but by now the careerist hustlers know they’d be better served by staying at home and striving to increase their follower/subscriber counts.

By now [2024], the suggestion that offline is the new online has become a little trite, but it’s no less true for that. The web in its evolved corporate playpen form has become the place where joy goes to die, but that destination needn’t be inevitable. Perhaps the photocopier’s hour has come again.

(1) 2000–2007: the lifespan of David Anez’s Bob and George. A coincidence, I’m sure.

Incidentally, my old comicking collaborator R. Wolff recently [2024] observed that sprite comics are to pre-Web 2.0 internet culture what the “swing revival” is to late nineties music:

Isn't it weird that nobody seems to talk about sprite comics anymore, even in the context of general 2000s nostalgia? I feel like they were an actual cultural touchpoint, extremely niche to be sure but also something you would have heard of in internet circles. They had an ecosystem and a scene and everything. And now in retrospect they're not even a blip on the cultural radar.

I’ll spare you my answer, but I had an answer.

(2) I couldn’t think of anywhere else to mention this, but the thumbnail on the frontpage is from Dan Miller’s Kid Radd.

Webtoons would have blown our damn minds.

Weiner redrew them and removed their original versions from the archives a very long time ago.

The inclusion of the vote button image shouldn’t be read as an endorsement of prurient schoolgirl gag strip Chugworth Academy. It only sticks in my memory because it (and its high ranking on webcomic popularity lists) got on my damn nerves.

There are illustrators who’d be drawing and sharing pics of dickgirl furries regardless of remuneration, but I’m not talking about them.

See BF Skinner’s Science and Human Behavior, chapter 6.

Oh this is so good, and so real. I wrote something similar recently, but I was a webcomics baby c2010-2014, right when the webcomics moneymaking boom kicked into high-gear. Do you remember the Pictures For Sad Children kickstarter meltdown? I think I emotionally flunked out of the whole merch-and-cons-and-kickstarter-print-runs grind about the same time and for similar reasons, and I've rarely made comics since. What you said about "offline is the new online" gives me hope, though-- it's encouraging to see other people recognizing how rancid social media platforms are in their current form, because maybe it means we can start building something better outside of them.

This, but for indie game making too. This, but for people who make music and put it online. This, but for video makers. This for everything :-(

And to your last point about offline being the new respite, https://samkriss.substack.com/p/the-internet-is-already-over *this*, but in a positive sense, has helped me the last few years.

In 2024, I have no facebook account, never use my moribund striver twitter and instagram accounts, enforce a pretty harsh news blackout on myself, try and fail a lot to quit reddit (I keep finding subreddits that bring me back for short periods), have given up most of my old favorite bloggers for lost, read no more webcomics (wow, Megatokyo, that's something I actually hadn't even thought of in more than a decade), and genuinely struggle to find content to read on the internet. I do watch a lot of youtube (and little traditional TV). Also sadly porn.

But in recompense, I have a pretty normie suburban house, wife, two kids, dog, time to ride my bike, time to design custom lego builds (themselves submitted to increasingly colonized online communities), and even a resurgent interest in actual reading.

It's not perfect - the two lives flicker in and out of my field of view more often and more unpredictably than I'd like - but I'll take a half great life half escaped from the fully colonized internet.