Though a century separates the careers of Karl Marx and Marshall McLuhan, there exists a broad area of overlap between the fields of activity they describe in their work.

Marx, perhaps working backwards to some extent, wanted to get to the bottom of the social causes and effects of the bourgeoisie revolution—how it incubated like an alien chestburster within the feudal order, how the productive powers of society were transformed and geometrically increased during the first industrial revolution, and the consequences of reorganizing nations around private firms seeking to extract surplus value from industrial labor in a condition of perpetual competition and metastability. McLuhan, on the other hand, was interested in technological paradigm shifts and their consequences in terms of how they alter our perceptions, social relations, and institutions.

In McLuhan’s telling, the invention of the Gutenberg press in the fifteenth century was the sine qua non of the social processes that would gradually converge and snowball into the capitalist system of organization. That system, anatomized by Marx, provided the productive crucible without which the electric media and consumer gadgets that so fascinated McLuhan could neither have been developed nor delivered unto the masses.

Both Marx and McLuhan focus their sights on technology and society, though they examine the subjects from radically different premises. It mightn’t be unfair to say that each of them works in one of the other’s blind spots. Communications media doesn’t much factor in to Marx’s worldview, and McLuhan felt that this oversight fatally hobbled him.1 I won’t presume to guess how Marx would have received McLuhan’s criticisms, but my educated guess is that such a precise and architectonic left-brain thinker as Karl would have found McLuhan’s oracular probes and mosaics sloppy and unserious, and would have vehemently rejected McLuhan’s contention that a technologically developed capitalist society clicks over into communism without the need for a proletarian uprising, and perhaps without anyone really noticing.2 Twentieth-century Marxist scholars, at any rate, were not McLuhan fans.

Where McLuhan is concerned, we can’t talk about how the electric media revolution changed society without first understanding print culture:

Psychically the printed book, an extension of the visual faculty, intensified perspective and the fixed point of view. Associated with the visual stress on point of view and the vanishing point that provides the illusion of perspective there comes another illusion that space is visual, uniform and continuous. The linearity precision and uniformity of the arrangement of movable types are inseparable from these great cultural forms and innovations of Renaissance experience. The new intensity of visual stress and private point of view in the first century of printing were united to the means of self-expression made possible by the typographic extension of man.

Socially, the typographic extension of man brought in nationalism, industrialism, mass markets, and universal literacy and education. For print presented an image of repeatable precision that inspired totally new forms of extending social energies. Print released great psychic and social energies in the Renaissance…by breaking the individual out of the traditional group while providing a model of how to add individual to individual in massive agglomeration of power. The same spirit of private enterprise that emboldened authors and artists to cultivate self-expression led other men to create giant corporations, both military and commercial.

Occasionally McLuhan’s terminology can be confusing: during its rise and ascendency in the West, print culture was both “explosive” and “centralizing.” It is explosive on the “molecular” level in that it that it disrupts the group-oriented, participatory, and emotional modality of the village and tribal situations, elevating the consciousness of the individual as such and promoting introspection and specialization over the extroversion and communality of a primarily oral culture. On the molar scale, however, it tends to centralize power and authority in metropolitan nodes hosting such institutions such as the university, the state bureaucracy, the Vatican, the East India House, and so on:

[T]he effect of the wheel and of paper in organizing new power structures was not to decentralize but to centralize. A speed-up in communications always enables a central authority to extend its operations to more distant margins. The introduction of alphabet and papyrus meant that many more people had to be trained as scribes and administrators. However, the resulting extension of homogenization and of uniform training did not come into play in the ancient or medieval world to any great degree. It was not really until the mechanization o( writing in the Renaissance that intensely unified and centralized power was possible.

Electric media, on the other hand, are implosive:

After three thousand years of specialist explosion and of increasing specialism and alienation in the technological extensions of our bodies, our world has become compressional by dramatic reversal. As electrically contracted, the globe is no more than a village. Electric speed in bringing all social and political functions together in a sudden implosion has heightened human awareness of responsibility to an intense degree. It is this implosive factor that alters the position of the Negro, the teen-ager, and some other groups. They can no longer be contained, in the political sense of limited association. They are now involved in our lives, as we in theirs, thanks to the electric media.

This is the Age of Anxiety for the reason of the electric implosion that compels commitment and participation, quite regardless of any “point of view.” The partial and specialized character of the viewpoint, however noble, will not serve at all in the electric age. At the information level the same upset has occurred with the substitution of the inclusive image for the mere viewpoint. If the nineteenth century was the age of the editorial chair, ours is the century of the psychiatrist's couch…

In the “implosion” of the electric age the separation of thought and feeling has come to seem as strange as the departmentalization of knowledge in schools and universities. Yet it was precisely the power to separate thought and feeling, to be able to act without reacting, that split literate man out of the tribal world of close family bonds in private and and social life.

Electronic mass media are then implosive because they reactivate the “tribal” sensibilities, compulsive involvement, and perhaps even the mythological perspective which print culture suppressed, or at the least left unnourished. The middle-aged of the 1960s shaking their heads and wondering what the hell the world was coming to were more or less like the buttoned-up young A-student, churchgoer, and teetotaler who inadvertently eats a weed brownie and feels his perspective of the world and his sense of himself convulsing. His sensory and cognitive apparatuses work differently than before; his behavior changes; his reasoning follows a different track, and new demands are incumbent upon him. An emergent media paradigm creates a similarly altered state of consciousness, which the population doesn’t come into all at once or even at a steady pace. Yesterday’s Romantics and Young Hegelians are today’s Breadtubers and TikTok intelligentsia.

The question is: do the “molecular” effects of implosive media entail a “molar” trend towards a decentralized society? (In vulgar Marxist terms, this is the same as asking if a formation in the superstructure can redound upon the base.)

McLuhan seemed to think so. He observes the effect of the telegraph in loosening the hold of the metropole over the province during the nineteenth century:

Even in England, where short distances and concentrated population made the railway a powerful agent of centralism, the monopoly of London was dissolved by the intervention of the telegraph, which now encouraged provincial competition. The telegraph freed the marginal provincial press from dependence on the big metropolitan press. In the whole field of the electric revolution, this pattern of decentralization appears in multiple guises.

By the mid-twentieth century, the “wheel and paper” effect (above) has gone into reverse, and McLuhan explicitly links implosion with decentralization:

Today with jet and electricity, urban centralism and specialism reverse into decentralism and interplay of social functions in ever more nonspecialist forms.

The wheel and the road are centralizers because they accelerate up to a point that ships cannot. But acceleration beyond a certain point, when it occurs by means of the automobile and the plane, creates decentralism in the midst of the older centralism. This is the origin of the urban chaos of our time. The wheel, pushed beyond a certain intensity of movement, no longer centralizes. All electric forms whatsoever have a decentralizing effect, cutting across the older mechanical patterns like a bagpipe in a symphony. It is too bad that Mr. [Lewis] Mumford has chosen the term “implosion” for the urban specialist explosion “Implosion” belongs to the electronic age, as it belonged to the prehistoric cultures. All primitive societies are implosive, like the spoken word. But “technology is explicitness,” as Lyman Bryson has said; and explicitness, or specialist extension of functions, is centralism and explosion of functions, and not implosion, contraction or simultaneity.

In 1969, at the end of the decade whose sturm und drang he’d predicted in advance, McLuhan gave an interview to Playboy. Here we find him at his most impishly provocative, and doubling down hard on his decentralist and tribal prognostications:

The U.S., which was the first nation in history to begin its national existence as a centralized and literate political entity, will now play the historical film backward, reeling into a multiplicity of decentralized Negro states, Indian states, regional states, linguistic and ethnic states, etc. Decentralism is today the burning issue in the 50 states, from the school crisis in New York City to the demands of the retribalized young that the oppressive multiversities be reduced to a human scale and the mass state be debureaucratized. The tribes and the bureaucracy are antithetical means of social organization and can never coexist peacefully; one must destroy and supplant the other, or neither will survive.

He also anticipates an end to the rule of the city over the country, identified by Marx and Engels as a self-reinforcing catalyst in the bourgeoisie revolution:

The transformations are taking place everywhere around us. As the old value systems crumble, so do all the institutional clothing and garb-age they fashioned. The cities, corporate extensions of our physical organs, are withering and being translated along with all other such extensions into information systems, as television and the jet—by compressing time and space—make all the world one village and destroy the old city-country dichotomy. New York, Chicago, Los Angeles—all will disappear like the dinosaur. The automobile, too, will soon be as obsolete as the cities it is currently strangling…The marketing systems and the stock market as we know them today will soon be dead as the dodo, and automation will end the traditional concept of the job, replacing it with a role, and giving men the breath of leisure. The electric media will create a world of dropouts from the old fragmented society, with its neatly compartmentalized analytic functions, and cause people to drop in to the new integrated global-village community.

Half a century and one more mass media revolution later, what do we say to that?

Reading early documents about the internet has the air of patristic studies. The netizen of the 2020s (and we are all of us netizens now) can’t but regard with wonder the missives and perspectives of that small minority of academics and tech nerds who were plugged in before the rest of us and had an inkling of what was to come.

One such exemplary document is Mitchell Kapor’s Foreword to the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s (Extended) Guide to the Internet, first published (posted?) in 1993. Though I urge you to read it—it’s a marvelous relic of early internet culture—here we’ll settle for just a few excerpts, once again with some key sentences bolded for skimmers.

Kapor begins:

New communities are being built today. You cannot see them, except on a computer screen. You cannot visit them, except through your keyboard. Their highways are wires and optical fibers; their language a series of ones and zeroes.

Yet these communities of cyberspace are as real and vibrant as any you could find on a globe or in an atlas. Those are real people on the other sides of those monitors. And freed from physical limitations, these people are developing new types of cohesive and effective communities - ones which are defined more by common interest and purpose than by an accident of geography, ones on which what really counts is what you say and think and feel, not how you look or talk or how old you are…

But how exactly does community grow out of a computer network? It does so because the network enables new forms of communication.

The most obvious example of these new digital communications media is electronic mail, but there are many others. We should begin to think of mailing lists, newsgroups, file and document archives, etc. as just the first generation of new forms of information and communications media. The digital media of computer networks, by virtue of their design and the enabling technology upon which they ride, are fundamentally different from the now dominant mass media of television, radio, newspapers and magazines. Digital communications media are inherently capable of being more interactive, more participatory, more egalitarian, more decentralized, and less hierarchical…

As such, the types of social relations and communities which can be built on these media share these characteristics. Computer networks encourage the active participation of individuals rather than the passive non-participation induced by television narcosis.

In mass media, the vast majority of participants are passive recipients of information. In digital communications media, the vast majority of participants are active creators of information as well as recipients. This type of symmetry has previously only been found in media like the telephone. But while the telephone is almost entirely a medium for private one-to-one communication, computer network applications such as electronic mailing lists, conferences, and bulletin boards, serve as a medium of group or "many-to-many" communication.

The new forums atop computer networks are the great levelers and reducers of organizational hierarchy. Each user has, at least in theory, access to every other user, and an equal chance to be heard. Some U.S. high-tech companies, such as Microsoft and Borland, already use this to good advantage: their CEO's -- Bill Gates and Philippe Kahn -- are directly accessible to all employees via electronic mail. This creates a sense that the voice of the individual employee really matters. More generally, when corporate communication is facilitated by electronic mail, decision-making processes can be far more inclusive and participatory.

Computer networks do not require tightly centralized administrative control. In fact, decentralization is necessary to enable rapid growth of the network itself. Tight controls strangle growth. This decentralization promotes inclusiveness, for it lowers barriers to entry for new parties wishing to join the network.

Given these characteristics, networks hold tremendous potential to enrich our collective cultural, political, and social lives and enhance democratic values everywhere.

Here Kapor encapsulates both the aspirations of early netizens and their belief that the new medium was intrinsically decentralizing.3 All early web culture had a bent just as he describes here. Webcomic artists and bloggers alike were at times almost ostentatiously critical of Old Media—the corporate publishers of superhero comics, the cable news programs, and the compromised journalists of the metropolitan papers of record. The filesharing community delighted in drinking the milkshakes and democratizing the products of record companies, academic journals, software developers, and so on—“information wants to be free” was their guiding credo. Personal websites and the message board galaxy were suffused with idiosyncrasy and folkishness. Nerds who were into video games and anime—media at which the majority still looked askance during the 1990s—created and participated in venues which ascribed a great deal of cultural importance to things like EarthBound and Sailor Moon, even though the rest of the mass media landscape and the populace at large didn’t give a damn about them.

We could go on. Notice how, contra McLuhan, Kapor sees television as a centralizing and passivizing medium. For the time being, let’s put that aside.

I’ve four thoughts about Kapor’s picture of the early nineties situation and his forecast of the medium’s future.

(1) A little later on the in document, Kapor writes:

In the current atmosphere of disaffection, alienation and cynicism, anything that promotes greater citizen involvement seems a good idea. People are turned off by politicians in general -- witness the original surge of support for Perot as outsider who would go in and clean up the mess -- and the idea of going right to the people is appealing, [sic]

What's wrong with this picture? The individual viewer is a passive recipient of the views of experts. The only action taken by the citizen is in expressing a preference for one of three pre-constructed alternatives. While this might be occasionally useful, it's unsophisticated and falls far short of the real potential of electronic democracy. We've been reduced to forming our judgments on the basis of mass media's portrayal of the personality and character of the candidates…

What I see in online debate are multiple active participants, not just experts, representing every point of view, in discussions that unfold over extended periods of time. What this shows is that, far from being alienated and disaffected from the political process, people like to talk and discuss -- and take action -- if they have the opportunity to do so. Mass media don't permit that. But these new media are more akin to a gathering around the cracker barrel at the general store -- only extended over hundreds, thousands of miles, in cyberspace, rather than in one physical location.

Skepticism toward “experts” was one consequence of electronic media which both McLuhan and Kapor saw coming. Insofar as the concept of “expertise” in a mass media society represents the centralization and hierarchizing of opinion, the internet has indeed had a democratizing impact here. This didn’t and couldn’t happen with the print and television ecosystems of McLuhan’s time. Papers of record and broadcast networks with national audiences might print opinion columns and interview guests representing different “expert” viewpoints on, say, the Vietnam War, but they weren’t going to give page space or airtime to heterodox armchair cranks who were utterly unknown in the milieus of government, academia, the military, publishing, etc., even if they happened to be intelligent, perceptive, and well-read cranks. The publishers and broadcasters were obliged to keep in mind some notion of a general audience as well as its perception of their institutional respectability.

Nowadays, the MAGA and anti-vax crowds famously disparage the opinions of experts and prefer to listen to voices from their own communities of belief. This is a matter of dire concern for people who own NPR tote bags and have stacks of New Yorker back-issues on their coffee tables, but it’s something they’re going to have to get used to. The centralized structures of the knowledge economy built up during the print epoch and largely preserved during the radio and television decades are under siege. For every accredited economist in the New York Times adducing the GDP and slowing inflation rates in an opinion column about the fundamental soundness of the United States’ economy, at least a dozen amateurs and trained dissenters are fiercely begging to differ on Twitter, TikTok, YouTube, Substack, etc. If anyone so chooses, they can skip reading the Times (and stop listening to its associated podcasts, viewing its YouTube content, etc.) altogether and opt to get their information from figures whose outlook aligns more with their own.

This isn’t the place to recite concerns about The Epistemological Crisis in much detail, but the fact is that the breakdown we’re seeing is part and parcel of the democratizing character of digital media.

(2) About that democratizing character, though.

Let’s think about a platform like Twitter, and about what we mean by “democracy.” On Twitter, every user can dispatch shortform observations, wisecracks, blurbs, etc. across the network. Obviously. But not all users and not all blurbs are equal.

Some users will have tens or hundreds of thousands of followers, and the content they submit will be received and at least momentarily considered by hundreds of thousands or millions of people. Other users will have six followers and their content will be seen and thought about by nobody. Some will select hundreds of people to follow, but will only be followbacked by a small fraction of them, and will remain more of an ear than a voice, regardless of what or how much they have to say.4 Some users hopped onto the platform after already achieving fame and/or notoriety in some other venue, and amassed a thousands-strong microblogging audience overnight.

On a platform like YouTube, we’re shown a grid of recommended videos based on our viewing history. We can toggle an opinion to have another video, selected on the basis of our measured preferences, begin to play as soon as the one we’re already watching ends. The algorithm also selects for quality, and in most cases quality is gauged by level of engagement, i.e., by how many other people like you have watched, liked, subscribed, commented, etc. I wonder if it’s even possible to train the algorithm to consistently feed a user uploads by obscure creators who have fewer than a hundred followers and whose videos have about as many views. But the system is democratic, is it not? More views, more votes, more visibility.

What I’m saying is that in cyberspace, everybody has a voice. That’s true. But on titanic platforms like Instagram, Twitter, and YouTube, some sort of sorting mechanism is necessary to prevent both unmitigated cacophony (such as you’d get if your Twitter feed were a chronological timeline of all users’ tweets) and the sort of sluggish, routinized monotony that would threaten engagement rates (such as you’d get if you followed fifteen people on Instagram and were fed nothing but those fifteen users’ posts). There’s certainly a shade of meritocracy in the way that effective users of a given platform see their content sweeping out increasingly broader arcs of circulation as their metrics increase—and much has been made of the equation of merit with aptitude for emotional manipulation on Facebook, Twitter, etc.—but we’re clearly no longer talking about anything even remotely resembling neighborly conversations around a virtual cracker barrel. In some respects, the medium has gone into reverse, recapitulating the one-way information flow from the publisher and broadcaster to the reader and viewer. A power user with over five hundred thousand followers is exceedingly unlikely to reply to your comment or question. They probably won’t even notice it. Chances are, the most you’ll get are some upvotes and maybe a reply or two from other viewers.

The short-sightedness of Kapor’s metaphor is astonishing, given his expectations of how large the web’s userbase would grow. Those cozy little bulletin boards he championed may have informed the templates of communication and community in cyberspace, but I suspect his libertarian outlook blinded him to the inevitability of their becoming dreadfully outmoded in about fifteen years’ time.

(3) Perhaps you noticed Kapor drawing a sharp distinction between online venues and mass media. To a young person who was born after the iPhone went on the market, this wouldn’t make even a lick of sense.

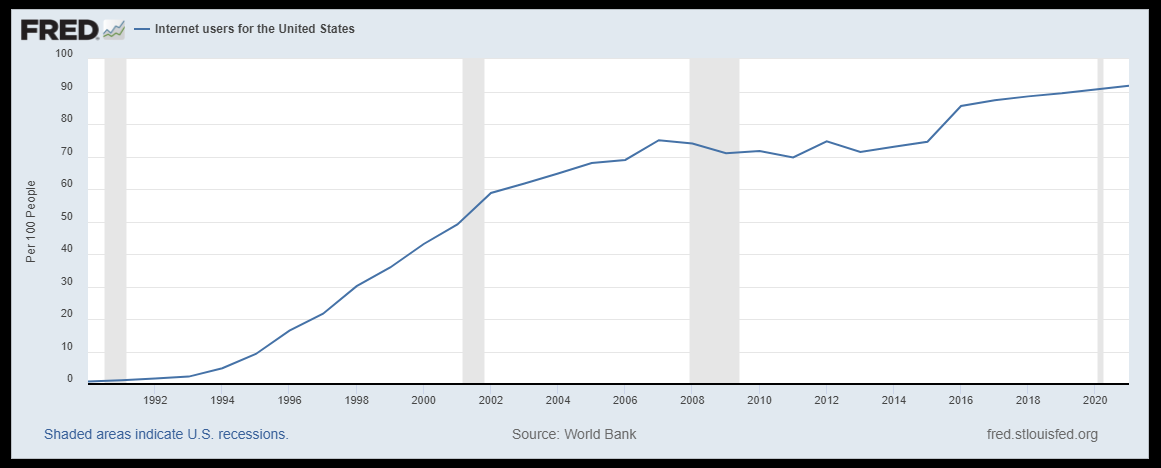

When Kapor typed out his foreword to the Guide to the Internet in 1993 (just two years after the World Wide Web was opened to the public) roughly two out of a hundred Americans had internet access. Of course the tenor of the chatter on bulletin boards and newsgroups would lend itself to analogies of Old West folk shooting the breeze on a covered porch in a small frontier town. If you were able to participate, you were either an academic or a computer nerd—so everybody involved had at least that much in common.

Consider: there were about 12 million American households tuned into The Simpsons in 1993. For the sake of convenience, let’s fudge the numbers and say one household equals one person. If we pretend that these twelve million viewers are representative of the 1993 public in that about two percent of them have internet access, that means there are roughly 24,000 people in the United States who are even capable of participating on the alt.tv.simpsons newsgroup. How many active posters do you suppose that translated to?

Frankly, I have no idea. The Slate article (linked above) says that there were 737 daily posts (a number which includes comments/replies) by 1997—and by 1997 there were already ten times as many internet users in the US than in 1993.

Just for fun, after typing that last sentence I counted up the number of posts and comments submitted to the subreddit dedicated to the comic book/Amazon series Invincible in the last twenty-four hours: about 2400.

If you were expecting a more impressive increase, do bear in mind that r/Invincible isn’t like the Simpsons newsgroup in 1993 or even in 1997 because it’s far from the only venue available to Invincible superfans. Go ahead and search for #invincible on Twitter or Tiktok and get back to me with some numbers, if you’d like. Tally the Invincible clips, reviews, and reaction videos uploaded to YouTube in the last week, and figure out how many comments they’ve all racked up. I can wait.

The FRED chart measuring the number of American internet users by year stops at 2021, when for every 100 people there were 91 with internet access, and the curve hadn’t yet flattened.

I had some remarks about what the overcrowding of the internet meant for its culture, but I’m going to save them for the next update. At any rate, in comparing the modern internet and its gigantic platforms to the bulletin boards and personal websites of the dial-up era, we’re skipping over the most critical phase in the web’s evolution.

(4) I’m going to quote a line from a 2023 Verge article about the web’s impending struggle to adapt to AI (a separate but not unrelated issue) because it articulates with such wonderful succinctness what happened in the late aughts:

Years ago, the web used to be a place where individuals made things. They made homepages, forums, and mailing lists, and a small bit of money with it. Then companies decided they could do things better. They created slick and feature-rich platforms and threw their doors open for anyone to join. They put boxes in front of us, and we filled those boxes with text and images, and people came to see the content of those boxes. The companies chased scale, because once enough people gather anywhere, there’s usually a way to make money off them.

Here is an important difference between how television and the internet developed as mass media. From the beginning, broadcast television was dominated by a triopoly: ABC, CBS, NBC. Each was already a national radio network and had the resources to expand into television after the second World War.

With the exception of America Online and its “gated community,” the landscape of internet content developed almost independently of the the conglomerates providing the telecommunications infrastructure and the computer hardware and software on which the web depended. The situation of the early internet was like an alternate timeline in which the national infrastructure supporting television had been erected during the 1950s, but all the programming had been left entirely up to amateurs working with microphones and cameras in the basements of the maintenance buildings next to all the broadcast antennae.

The rise of the platforms represented the arrival of capital on the scene in full force, heralding the end of the dispersed Wild West internet. By the early 2010s, the web had become centralized around a small number of platforms and services owned and operated by mind-bogglingly wealthy firms, and all user content had to conform to whatever parameters they chose to set.

Joshua Meyrowitz, an admirer of McLuhan, had a different outlook on what happens during an information revolution. When patterns of information access are altered in such a way that bypasses entrenched institutions and authorities, it follows that those entities are weakened. The printing press busted the medieval church’s monopoly on knowledge production; the motion picture camera sucked the life out of the playhouse; radio terrorized early twentieth-century newspapers. The disruption of longstanding economic, cultural, and political power structures precipitates some lesser or greater degree of anarchy in which actors situated at a distance from the center(s) can use previously unavailable resources, take advantage of new opportunities, and otherwise move and act in ways from which they had been restricted. But this usually plays out as an energetic interval between the breakdown of one form of hierarchical organization and the hardening of another.

As I’ve said before, a miniature version of this process played out during the anarchic early days of the webcomic. “Publishers? We don’t need no stinking publishers! We’ll draw and write whatever the hell we please and put it on the internet!” The gatekeepers of Old Media were thus bypassed, and new audiences were sought and found.

After a few years, the cream rose to the top. For the newbie webcomic artist, this more often meant that a good strategy for getting your own stuff noticed was to seek out the successful artists, ingratiate yourself to them, try to get them to add your comic to their links pages (and naturally you’d make a point of linking readers to their site), participate on their message boards and look for opportunities to tactfully promote your work to their fans—and so on. All of this had the effect of reinforcing the emergent hierarchy; the small comics all pointed towards the big comics, and the big comics all pointed towards each other. As the years went by, I became less surprised whenever I noticed recognizable names from the webcomics scene on the covers of print matter at Barnes & Noble.

Something a little bit like this played out during the Web 2.0 transformation, though on a scale that was at once much larger and much more in line with Marx’s description of capitalist consolidation. It’s been interesting to watch some of the other people who used to write longform pieces about Final Fantasy for personal websites or small-scale blogs reinventing themselves as YouTubers, because they didn’t have much of an alternative. If they wanted to stay in business, they had to essentially become contracted employees of Alphabet whose earnings are contingent on how much business they bring to the platform. Sure, YouTube only asks for a 45 percent cut of their ad revenue, but that’s still 45 percent more than they were giving up if and when they sold banner and sidebar ad space through email links on sites which they themselves operated. Even if the modern internet’s economy of scale means that the successful YouTuber has a substantially larger audience and earns a lot more than the “successful” content creator of 2005 (in quotes because, comparatively speaking, he or she was a lonely pauper), it also means that it’s virtually impossible for anyone who makes things on the internet to bypass the big platforms and have much of an audience or much hope of earning an income for their work.5

According to leftist economist Yanis Varoufakis, Alphabet, Amazon, Meta, and the other winners of the digital revolution don’t simply represent the latest incarnation of monopoly capitalism, but are like those Magic: The Gathering players who occasionally hit upon some overlooked combination of cards that make the game unwinnable for everyone else. They’ve stacked their decks and played their hands so perfectly, they’ve so successfully dominated the field and distorted both the media environment and the economy that they’ve altogether broken the game. If Varoufakis is to be believed, Big Tech represents the end of capitalism and the inauguration of a technofeudalist regime in which users, consumers, workers, and even traditional capitalists are reduced to a kind of serfdom.6 Whether or not we believe him on that account, there’s no denying that anyone who participates in society has no choice but to do business with Big Tech, and Big Tech always comes out the winner in any bargains made with it. Moreover, try to imagine the depth and breadth of the resources Alphabet, Amazon, and Meta could marshal against democratic governments and politicians that presume to try bringing them to heel.

On the question of centralization, McLuhan was wrong and Marx was right. A populace that has in some sense been (re)tribalized needn’t necessarily insist in their words or by their actions a dispersal of existing power and authority, especially when virtually all of their daily activities directly or indirectly empower and keep it in place.

It’s all the same to Alphabet whether you’re watching Contrapoints, Ben Shapiro, Norm Finkelstein, or Destiny on YouTube; Meta doesn’t care what you’re telling your abstract idea of an audience in your Instagram stories, so long as you say it in a way that makes users keep the app open for another thirty seconds.7 In any case, you’re still using the products, bartering your data, training the algorithms, and supplying a trickle of income that converges with a billion others to thunder into the firms’ coffers as a monstrous cascade—some of which Alphabet and Meta subsequently funnel towards developing The Next Big Thing that must inevitably consolidate wealth and mobility in fewer hands. The “disruptions” effectuated by Big Tech have ever only slanted the field towards an economic centralization that translates into irresistible social and political power. After all—if Alphabet, Meta, or OpenAI decides to develop an AI that will put two out of every three people in your field out of work, and make life worse for those who remain, do you suppose anyone could stop them?

The digital revolution represents the perfection of the synthesis between mass culture and monopoly capitalism.

(1) McLuhan:

[Marx and his followers] reckoned without understanding the dynamics of the new media of communication. Marx based his analysis most untimely on the machine, just as the telegraph and other implosive forms began to reverse the mechanical dynamic.

(Unless noted otherwise, all the McLuhan quotes are from Understanding Media.)

(2) I have not read every word Marx ever wrote, and his output was titanic. I’m sure McLuhan didn’t read a lot of Marx either, but he would have surely given his approval to these lines from a letter Marx wrote to Engels which I recently happened upon. (I’ve boldfaced a couple of bits if you’d prefer to skim rather than to peruse.)

Re-reading my technological and historical excerpts has led me to the conclusion that, aside from the invention of gunpowder, the compass and printing — those necessary prerequisites of bourgeois progress — the two material bases upon which the preparatory work for mechanised industry in the sphere of manufacturing was done between the sixteenth and the mid-eighteenth century, i.e. the period during which manufacturing evolved from a handicraft to big industry proper, were the clock and the mill (initially the flour mill and, more specifically, the water mill), both inherited from Antiquity. (The water mill was brought to Rome from Asia Minor in Julius Caesar’s time.) The clock was the first automatic device to be used for practical purposes, and from it the whole theory of the production of regular motion evolved. By its very nature, it is based on a combination of the artist-craftsman’s work and direct theory. Cardan, for instance, wrote about clock-making (and provided practical instructions). German sixteenth-century writers describe clock-making as a ‘scientific (non-guild) handicraft’, and, from the development of the clock, it could be shown how very different is the handicraft-based relation between book-learning and practice from that, e.g., in big industry. Nor can there be any doubt that it was the clock which, in the eighteenth century, first suggested the application of automatic devices (in fact, actuated by springs) in production. It is historically demonstrable that Vaucanson’s experiments in this field stimulated the imagination of English inventors to a remarkable extent.

McLuhan (bolds mine):

When Europeans used to visit America before the Second War they would say, “But you have communism here!” What they meant was that we not only had standardized goods, but everybody had them. Our millionaires not only ate cornflakes and hot dogs, but really thought of themselves as middle-class people. What else? How could a millionaire be anything but “middle-class” in America unless he had the creative imagination of an artist to make a unique life for himself? Is it strange that Europeans should associate uniformity of environment and commodities with communism? And that Lloyd Warner and his associates, in their studies of American cities, should speak of the American class system in terms of income? The highest income cannot liberate a North American from his “middle-class” life. The lowest income gives everybody a considerable piece of the same middle-class existence. That is, we really have homogenized our schools and factories and cities and entertainment to a great extent, just because we are literate and do accept the logic of uniformity and homogeneity that is inherent in Gutenberg technology. This logic, which had never been accepted in Europe until very recently, has suddenly been questioned in America, since the tactile mesh of the TV mosaic has begun to permeate the American sensorium. When a popular writer can, with confidence, decry the use of the car for travel as making the driver “more and more common,” the fabric of American life has been questioned.

Moreover, the document as a whole evinces the Californian Ideology. Kapor was in fact the founder and CEO of Lotus, which developed the once-ubiquitous spreadsheet software that was squashed by Microsoft Excel in the 1990s. Now he’s a venture capitalist.

Some people just aren’t good at Twitter. (An inherent problem of any medium is that some people are better at using it than others. For instance, there were the silent film actors whose aptitude for that format simply didn’t translate into talkies. Not every blogger of the 2000s and 2010s is cut out to be a YouTuber or TikTokker.)

(he says on his Substack)

If you own a company that manufactures products to be sold for a profit, good luck trying to bypass Amazon and avoid giving Jeff Bezos his cut. (This is the partial basis of the FTC’s antitrust case; the agency alleges that Amazon actually increases consumer prices as vendors and sellers charge more to compensate for the rents Bezos extracts from them.)

Moreover, Jeff Bezos knows he needn’t worry if a hundred thousand people stage a protest against his business practices by not buying anything from Amazon for a week or a month. He has every reason to be confident that most of them will come crawling back afterwards.