A collage of excerpts, pasted around a few common themes:

OBJECT A

In late January 1848, the French politician Alexis de Tocqueville (best known today for penning Democracy in America) exhorted his colleagues in the Chamber of Deputies to pay attention to the gigantic wasps’ nest thrumming beneath their picnic table:

…I am told that there is no danger because there are no riots; I am told that, because there is no visible disorder on the surface of society, there is no revolution at hand…Do you not see that the [working classes] are gradually forming opinions and ideas which are destined not only to upset this or that law, ministry, or even form of government, but society itself, until it totters upon the foundations on which it rests today?

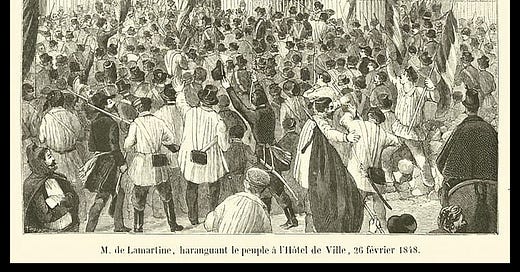

None of his compeers took him seriously. A few weeks later, the French government was overthrown after only four days of street fighting in Paris. King Louise Phillipe I abdicated the throne and fled the country. The insurrectionists established the Second Republic on February 24.

The Austrian chancellor Klemens von Metternich, the architect and avatar of Europe’s conservative post-Napoleonic status quo, once observed that “when France sneezes, the rest of Europe catches cold.” 1848 proved him right in the worst kind of way—or the best kind of way, depending on how you feel about police states. A month after the eruption in Paris, rioters in Vienna forced Metternich into resignation and exile.

Every nation convulsed by the pan-European revolutionary wave had its own particular circumstances, but there were several common themes throughout. Economic crises. The pangs of industrialization and urbanization. Censorship regimes, repressive policing, and bans on public assembly—all aimed at suppressing political opposition. The nationalistic aspirations of peoples living in politically partitioned countries (Germany and Italy) or under foreign rule (Hungary and Poland). Liberal trends in public opinion and the swelling interest in political participation, both stoked by increasing literacy rates, grinding up against paranoid monarchical regimes and stringently prohibitive criteria for suffrage.

In October 1848, the French anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, elected to the new Constituent Assembly in June, gave his celebrated “A Toast to the Revolution” speech:

Citizens, I swear it by Christ and by our fathers! Justice has sounded its fourth hour, and misfortune to those who have not heard the call!

— Revolution of 1848, what do you call yourself?

— I am the right to work!

— What is your flag?

— Association!

— And your motto?

— Equality before fortune!

— Where are you taking us?

— To Brotherhood!

— Salut to you, Revolution! I will serve you as I have served God, as I have served Philosophy and Liberty, with all my heart, with all my soul, with all my intelligence and my courage, and will have no other sovereign and ruler than you!

In spite of its ecstatic tone, Proudhon’s address was an attempt at injecting some rhetorical fuel into a movement that had already lost its momentum. Louis Napoleon Bonaparte III would be elected president in December, and in less than four years he’d proclaim himself emperor and close the chapter on the Second Republic.

To make a (very) long story short: Europe’s revolutionary fever broke in less than two years. The uprisings were thwarted and reversed.

Charles Breunig’s The Age of Revolution and Reaction, 1789–1850 (an old but serviceable book I’ve had on my shelf for many years) sums up the winter which immediately followed the Spring of Nations:

By December, 1848, the revolutionaries had been defeated or were fighting rearguard actions almost everywhere in Europe. The overthrown dynasty was not restored in France, but in December the first presidential election under the new republican constitution resulted in an overwhelming victory for Louis Napoleon Bonaparte, who emerged as a symbol of order for many Frenchmen frightened by the bloodshed and social upheaval that had occurred earlier in the year. Another eight months passed before the Hapsburg monarchy, with the aid of Russian troops, suppressed the revolt in Hungary. In the early months of 1849 the Sardinians renewed their struggled against Austria for the liberation of Italian territory, and elsewhere in the peninsula the Roman Republic was proclaimed. But these were short-lived episodes which merely prolonged the revolutionary agony but could not reverse the general trend. By the end of 1849 the counterrevolution was everywhere triumphant. To the bitterly disillusioned revolutionaries it seemed that nothing had been gained. In fact, the situation in many countries appeared worse than it had been before the revolts. Where constitutions had been granted they were either suspended or rendered ineffectual. Revolutionary leaders were imprisoned or exiled and the freedoms for which they had fought were systematically denied…

In a 2019 lecture hosted by the London Review of Books, historian Christopher Clark argues that the pessimistic outlook was overstated. Though triumphant, the old order could not reinstate the pre-1848 state of affairs. The surface-level revolutionary conflagrations may have been extinguished, but the transfer of their residual heat persisted through subterranean channels:

The true legacy of 1848 on the European continent is to be seen in the breadth of administrative change triggered by the upheavals. Pragmatic centrist coalitions emerged in the aftermath of the turmoil: the…marriage between the left liberals and the flexible conservatives in Piedmont, in which Cavour was involved; the Unión Liberal in Spain; the Regeneração in Portugal. Formations whose rhetoric and outlook marked a clear departure from the ideologically polarized positions of left and right in the pre-March era, the pre-1848 era.

The rigid and unimaginative official censorship regimes of the Restoration gave way to a more nimble, collaborative, and systematic approach to the press. Governments scaled down the censorship apparatuses of the 1840s, and went instead for systems of information management involving media subsidies and the structured siphoning of news stories to selected newspaper editors.

To a greater extent than ever before, the European governments of the post-revolutionary years legitimated themselves by reference to their capacity to stimulate and sustain economic growth. They refurbished Europe's cities, from Paris (transformed by Haussmann), to Vienna (where the old city walls were demolished to create space for the Ringstrasse), to Madrid (where the urban planners Mesonero and Castro transformed the inner city). They launched public works projects on a scale that exceeded anything attempted during the Restoration era. They established a technocratic romanticism focused on the improvement of infrastructure and the pursuit of a form of material progress that would make the polarized politics of the 1840s obsolete—or so at least they hoped.

In other words…the revolutions of 1848 may have ended in failure, marginalization, exile, imprisonment, even death for some of their protagonists, but their momentum communicated itself like a seismic wave to the fabric of the European administrations, changing structures and ideas, bringing new priorities into government, or reorganizing old ones, reframing political debates. The Vienna-based political theorist Lorenz von Stein captured the meaning of these changes when he observed that as a consequence of the revolutions, Europe had passed from what he called the Zeitalter der Verfassungen—the age of constitution—to the Zeitalter der Verwaltung—to the age of administration.

And the enabling phenomenon at the core of this transformation was the ascendancy of the political center over the polarized formations of left and right that had dominated the 1840s. Many radicals and conservatives moved inwards from the fringes to affiliate with centrist groups close to the state. Those who did not risked irrelevance and even ridicule. The result was a new kind of politics—uma nova política, as the Portuguese Regenerators were fond of saying…

To these, we ought to add another aftereffect of the spring of nations: the working classes’ arrival at the grim realization that they were on their own. Bruenig again:

Perhaps the most unequivocal consequence of the failure of the revolutions of 1848 was the destruction of working-class hopes and illusions. With their leaders dead, in hiding, or in exile, the workers did appear [as Proudhon wrote] “beaten and humiliated…scattered, imprisoned, disarmed, and gagged.” … Karl Marx, writing of the revolt in France, declared, “The February republic finally brought the rule of the bourgeoisie clearly into prominence, since it struck off the crown behind which Capital kept itself concealed.” … Up until 1848 [workers] had more often than not been allied with the middle class against the old order, and they fought on the same side of the barricades in many places during the initial phases of the uprisings. But as the revolts progressed, the bourgeoisie, increasingly concerned over the extremism of the mob and the alleged threat to private property, tended to line up with the old order or at least with those intent upon suppressing the threat of a thoroughgoing social revolution. In time, the bitterness and class antagonisms created by the events of 1848 declined, but the possibilities for genuine collaboration between capitalist and proletarian, employer and employee, were never quite the same.

OBJECT B

While the unrest of the 1960s was a global phenomenon, we’ll just focus on the United States.

You’re familiar with the imagery, the sounds, the names, the slogans of the Sixties. Hippies, Hell’s Angels, Bob Dylan, hell no we won’t go, florid psychedelia, get out of Saigon and into Selma, riot police, longhairs, free love, the Black Panthers, Timothy Leary, Students for a Democratic Society, etc. Taken in its broadest outlines, the Movement was an outraged generational response to Cold War conservatism, the Vietnam War, the brutal institutionalized racism of the South, and unresponsive civic institutions and untrustworthy authority figures in general.

The counterculture as a political forced received its mortal blow in 1968 amid the chaos of the Democratic National Convention and the victory of the “silent majority” over the radical minority in the election of GOP presidential candidate Richard Nixon. The agitators, activists, and dissidents hobbled on for a while longer, but by the early 1970s their strength was exhausted and their cohesion unraveled.

In Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, a literary funeral dirge for 1960s, Hunter Thompson reminisces on the Californian spirit of the time:

There was madness in any direction, at any hour. If not across the Bay, then up the Golden Gate or down 101 to Los Altos or La Honda. . . . You could strike sparks anywhere. There was a fantastic universal sense that whatever we were doing was right, that we were winning. . . .

And that, I think, was the handle—that sense of inevitable victory over the forces of Old and Evil. Not in any mean or military sense; we didn’t need that. Our energy would simply prevail. There was no point in fighting—on our side or theirs. We had all the momentum; we were riding the crest of a high and beautiful wave. . . .

Thompson attributes the failure of the Movement not so much to tear gas and truncheons administered from above, but to divisions from within:

One of the crucial moments of the Sixties came on that day when the Beatles cast their lot with the Maharishi. It was like Dylan going to the Vatican to kiss the Pope’s ring.

First “gurus.” Then, when that didn’t work, back to Jesus. And now, following Manson’s primitive/instinct lead, a whole new wave of clan-type commune Gods like Mel Lyman, ruler of Avatar, and What’s His Name who runs “Spirit and Flesh.”

Sonny Barger never quite got the hang of it, but he’ll never know how close he was to a king-hell breakthrough. The Angels blew it in 1965, at the Oakland-Berkeley line, when they acted on Barger’s hardhat, con-boss instincts and attacked the front ranks of an anti-war march. This proved to be an historic schism in the then Rising Tide of the Youth Movement of the Sixties. It was the first open break between the Greasers and the Longhairs, and the importance of that break can be read in the history of SDS, which eventually destroyed itself in the doomed effort to reconcile the interests of the lower/working class biker/dropout types and the upper/middle, Berkeley/student activists.

Nobody involved in that scene, at the time, could possibly have foreseen the Implications of the Ginsberg/Kesey failure to persuade the Hell’s Angels to join forces with the radical Left from Berkeley. The final split came at Altamont, four years later, but by that time it had long been clear to everybody except a handful of rock industry dopers and the national press. The orgy of violence at Altamont merely dramatized the problem. The realities were already fixed; the illness was understood to be terminal, and the energies of The Movement were long since aggressively dissipated by the rush to self-preservation.

Regarding “the history of SDS:” activist and filmmaker Geoff Bailey elaborates on the conflicting factions within Students for a Democratic Society, and points to the glaring problem which doomed its revolutionary aspirations from the start:

In 1968, the revolutionary left exploded. What had been a movement that prided itself in being non-ideological quickly turned to revolutionary politics:

Propelled both by the escalating crisis in American society and by the manifest bankruptcy of its earlier liberal, reform-oriented approach, SDS politics went through a very rapid evolution to the left, from liberal protest in 1964 (“Half the Way with LBJ”), to anti-imperialist resistance in 1967, to varieties of anti-capitalist revolutionism today [1969]. What began as a movement in many ways resembling a super-idealistic children's crusade to save the world, was becoming increasingly grim and increasingly serious.

According to one poll in 1969, more than one million students considered themselves revolutionaries and socialists of some kind. The debates of the Old Left—reform versus revolution, the working class and the need for a revolutionary party—now took on new significance. In the fall of 1968, more that 350,000 said that they strongly agreed with the statement that some form of "mass revolutionary party" was needed in America. SDS reached a peak of 100,000 members; and then it collapsed almost as quickly as it had risen. At its national convention in 1969, SDS split into two rival factions, one dominated by the Maoist-turned-Stalinist Progressive Labor Party (PL) and the other called the Revolutionary Youth Movement (RYM), which promptly split into two rival factions itself…

The basic problem was that student radicals had come to the conclusion that a revolution was needed—that war, racism and poverty were not simply bad policies, but were the outgrowth of a system based on the exploitation of the vast majority for the benefit of a small minority, and that system could not be changed through the existing channels of the Democratic Party. But the movement didn't have the power to make a revolution. Students could shut down the universities. They could battle the cops in the street and get media coverage. They could force the issue of the war into the mainstream—which was no small feat given the corporate control of the media—but they didn't have the social power to bring to bear on a ruling class that could not afford to lose Vietnam.

And so the engine ran out of steam. The radical politics of the decade proved untenable. As Professor Clark said of the vestiges of Europe’s radical element in the counterrevolution’s aftermath, irrelevance and ridicule awaited the activists and gadflies who wouldn’t or couldn’t reorient themselves towards the center during the 1970s. Aspersions of left-radicalism were instrumental in ensuring George McGovern’s crushing loss to Nixon in the 1972 presidential election. During the century’s latter decades, the hippie—the the pop-cultural face of the 1960s counterculture—endured as a stock character in television, appearing as a fogbrained, ineffectual, and out-of-touch middle-aged man.

An attitude of realism filled the vacuum left by the deflated aspirations of the Movement—one which informed the post-sixties trajectory of quondam radicals and activists who provided the factual template for Stevo’s father in the film SLC Punk. “I didn’t sell out, son. I bought in.”

In No Sense of Place, Joshua Meyrowitz observes that the visible recession of the tidal wave drew attention away from the social undercurrents which coursed on, unimpeded, in the same direction as before:

[T]he 1970s and 1980s have been a continuation, rather than a reversal, of the 1960s. The “gestalt” of the 1960s may be gone, the Utopian political and social rhetoric may have disappeared, but the basic situational dynamics continue to lead to adjustments in social behavior…Sit-ins, T-shirts, slogans, demands for freedom, equality, and justice are still everyday sights and sounds, but there is no longer any amazement or shock. These tactics are used by the police, handicapped, rednecks, farmers, homosexuals, and the elderly. The Movement is dead; but it lives on its many diverse offspring. Now the single massive line of confrontation (and solidarity) is gone. It is no longer young versus old, yippies versus “pigs,” hippies versus rednecks…

Contrary to many claims, the former protestors have not simply settled down or “sold out”; instead many of their “offensive behaviors” and “unpatriotic beliefs” have been incorporated into the system. The 1960s “counterculture” was characterized by its antiwar protests, its distrust of authority, its looser sexual mores, and its use of illicit drugs. Many of these behaviors and beliefs have become part of mainstream America…

In many ways…the Movement and the Establishment have merged into a “middle region” system that has elements of both. Radicals of the 1960s run for political office, and judges and corporate executives smoke marijuana and use cocaine. Congress finishes some of the work started by the protestors who camped at the Washington monument: It investigates the abuses of the CIA and FBI, intimidates a President into resigning from office, and tries to curb the government’s covert operations against other countries. Blacks take over the mayoralty of major cities such as Atlanta, Chicago, Philadelphia, and Los Angeles, and former racist politicians beg blacks for forgiveness and support. And the basic distrust of government and authorities, which characterized The Movement, has now spread throughout large segments of the total population…

The [student] protests of the 1960s may have quieted down, but perhaps only because there has been a dramatic shift in the balance of authority. Young students today do have more of a say in the workings of society….While ‘60s-style student demonstrations have largely (though not completely) disappeared, lobbying and litigation have increased dramatically…Student involvement in the workings of society is still great, perhaps even greater than it was in the 1960s.

It’s worth noting that No Sense of Place was published in 1985—a year after the same generational cohort that listened to Bob “Don’t Trust Anyone Over 30” Dylan, grew out its hair, smoked grass, and staged demonstrations against segregation, Vietnam, and the suppression of speech in the 1960s voted to give the Gipper a second term. We should also point out that Meyrowitz perhaps wasn’t in a position to observe the apotheosis of the Movement/Establishment synthesis in the form of the Californian ideology, that Luciferian union of 1960s social libertarianism and 1980s economic libertarianism which has animated the culture of Silicon Valley since its early years.

Footnote: as far as the college radicals were concerned, the working classes were an afterthought from the beginning. Bailey again:

SDS activists were influenced more by the ideas of sociologist C. Wright Mills than those of Karl Marx. They attacked the stultifying bureaucratism of corporate liberalism and promoted decentralized decision making and semi-communal living. The latter, argued Hayden,

stems from the need to create a personal and group identity that can survive both the temptations and the crippling effects of this society. Power in America is abdicated by individuals to top-down organizational units, and it is in the recovery of this power that the movement becomes distinct from the rest of the country and a new kind of man emerges.

American workers were seen as, at best, bought off by the system and, at worst, part of the problem. A challenge to the existing order would have to come from “marginalized elements,” a vague concept whose definition would change over the course of the decade from “the poor,” to radical students, to movements in the Third World…New Left activists rejected the ideologies of the Old Left and of Marxism. The ideas of workers’ power, class struggle and working class self-emancipation were seen as irrelevant, though it was much less clear what was to replace them.

OBJECT C

I don’t suppose our memory has been so rotted by the internet that the Occupy movement needs a lengthy reintroduction.

Against the background of the Global Financial Crisis, the Obama administration’s unwillingness to prosecute any of the firms or figures that recklessly tanked the economy, the ascendency of the reactionary Tea Party movement, and the victories of the Arab Spring, the magazine Adbusters printed a mysterious #occupywallstreet poster in its 97th issue and sent out a mass email:

Alright you 90,000 redeemers, rebels and radicals out there,

A worldwide shift in revolutionary tactics is underway right now that bodes well for the future. The spirit of this fresh tactic, a fusion of Tahrir with the acampadas of Spain, is captured in this quote:

“The antiglobalization movement was the first step on the road. Back then our model was to attack the system like a pack of wolves. There was an alpha male, a wolf who led the pack, and those who followed behind. Now the model has evolved. Today we are one big swarm of people.”— Raimundo Viejo, Pompeu Fabra University, Barcelona, Spain

The beauty of this new formula, and what makes this novel tactic exciting, is its pragmatic simplicity: we talk to each other in various physical gatherings and virtual people’s assemblies … we zero in on what our one demand will be, a demand that awakens the imagination and, if achieved, would propel us toward the radical democracy of the future … and then we go out and seize a square of singular symbolic significance and put our asses on the line to make it happen.

The time has come to deploy this emerging stratagem against the greatest corrupter of our democracy: Wall Street, the financial Gomorrah of America.

On September 17, we want to see 20,000 people flood into lower Manhattan, set up tents, kitchens, peaceful barricades and occupy Wall Street for a few months. Once there, we shall incessantly repeat one simple demand in a plurality of voices.

Tahrir succeeded in large part because the people of Egypt made a straightforward ultimatum – that Mubarak must go – over and over again until they won. Following this model, what is our equally uncomplicated demand?

The most exciting candidate that we’ve heard so far is one that gets at the core of why the American political establishment is currently unworthy of being called a democracy: we demand that Barack Obama ordain a Presidential Commission tasked with ending the influence money has over our representatives in Washington. It’s time for DEMOCRACY NOT CORPORATOCRACY, we’re doomed without it.

This demand seems to capture the current national mood because cleaning up corruption in Washington is something all Americans, right and left, yearn for and can stand behind. If we hang in there, 20,000-strong, week after week against every police and National Guard effort to expel us from Wall Street, it would be impossible for Obama to ignore us. Our government would be forced to choose publicly between the will of the people and the lucre of the corporations.

…Beginning from one simple demand – a presidential commission to separate money from politics – we start setting the agenda for a new America.

The “redeemers, rebels and radicals” descended upon Manhattan’s Zuccotti Park on September 17. In the following weeks, protestors in cities across the United States set up camps and conducted marches and demonstrations of their own. The hacker group Anonymous, at the height of its dangerous allure, issued statements in support of the protesters and warned law enforcement to tread carefully. Messaging calling attention to the economic upper percentile and its grossly disproportionate share of national wealth—the 1% versus the 99%—forced class consciousness into the American zeitgeist for the first time in decades.

A Pew poll released on October 24 found that 39% of the public supported Occupy Wall Street, while 35% were opposed to it. In both regards, it rated better than the astroturfed Tea Party “movement.” In a CBS poll published two days later, 43% of respondents approved of Occupy’s views, while 27% disapproved. In both cases, the high percentages of respondents answering “neither” or “don’t know” should have been a cause for deep concern among the activist camps.

Nota bene—the movement’s original “manifesto” stated “one simple demand:” an end to pay-to-play politics, corporatocracy, oligarchy, whatever you’d like to call it. As the movement grew and the camps’ numbers swelled, the occupiers’ multiplying demands grew markedly less simple. “A presidential commission to separate money from politics” may have been part of the developing conversation, but it was hard to say. It depended on your vantage point, and on which message(s) reached you.

While the occupiers within the bubble-realities of the camps were living the change they wanted to see in the world—“riding the crest of a high and beautiful wave”—their “semireligious” rejection of vertical leadership structures and refusal to engage in conventional politics (“We can have a voice without having demands”) scattered the movement’s energy unto dissipation. As soon as the initial shock wore off, the tent cities, the marches, and the drum circles amounted to localized disruptions and media chatter which applied no substantial pressure upon the movement’s stated targets on Wall Street and in Washington.

The Zuccotti Park encampment was busted up on November 15, shortly after midnight. Some of the occupiers and activists regrouped, promising the fight wasn’t done. Over the next few months, efforts to re-occupy the space were intercepted and frustrated by law enforcement. The other cities’ encampments were likewise cleared away. By winter’s end, Occupy was spoken of in the past tense.

In retrospect, the most obvious legacy of Occupy was the shape of the 2016 presidential contest. Both the Democratic and Republican primaries were upstaged by populist firebrands vociferating about a broken political system rigged by insider clubs and moneyed interests. The party that failed to suppress its maverick and nominate an establishment candidate ended up taking the White House. (Of course, as an economic reformist, Trump was—as he is in every other regard—an unprincipled charlatan.) The Occupy movement may have been quashed, but its unaddressed casus belli still rankled the electorate.

But Occupy signaled another and perhaps more profound transformation in American politics and culture. Below is an excerpt from a statement issued by the People of Color Working Group at Occupy K Street, the Occupy “franchise” that operated in Washington, DC. Note that conversations along these lines were not restricted to this one encampment.

The following are a list of grievances that we would like to make public about incidences and phenomena that we have witnessed at Occupy K St. We hope that by seeing this you will understand the dire need to bring issues of privilege, oppression, and entitlement into the open to frame an inclusive, more effective movement.

The language of occupation is problematic. Washington, DC has seen four waves of occupation: the theft of land from its original inhabitants, the oppression of the government’s establishment in the city to the people of color who are resident of the city, the white people who now occupy areas as part of gentrification, and, now, by the middle class white people who are intending to “occupy” McPherson Square. In addition white people calling the economic oppression they experience “slavery” and using symbolism reminiscent of chattel slavery.

Cis-men complaining about being asked to inquire about pronoun preference instead using gendered familiar language such as “dear” or “hon”.

White men claiming they understand racial oppression because they have experienced “reverse racism” or other types of oppression, that they don’t see color or that we are living in post-racial America, that class is more important than race, that bringing up slavery is dwelling on the past and that they can’t possibly be perpetuating racism because they “have a black friend”.

White people approaching people from marginalized groups and insisting that they find solutions for making spaces inclusive and then instructing those people how they should feel, act, think.

A woman of color being told to “get in your place”. White men complaining about women “taking up too much space” and threatening to tear down a safer spaces tent.

Men of color being racially profiled and falsely accused of wrongdoing.

People who perpetuate oppression defending their behavior rather than listening and being open to change. White men expressing opposition to the use of progressive stack. A proposal that stated that members of a committee “should attend anti-oppression training and anti-racist groups” being blocked by an individual who also refused to encourage marginalized people to attend the meeting before the GA.

Women being talked over, shouted down, ignored, dismissed, threatened, harassed, etc. and in one instance being told by men that they “don’t see gender – therefore women’s issues aren’t a problem” and in another having her biographical information sent over a listserv to strangers.

An inability to address issues that arise from sharing the space with people who are homeless, some of whom suffer from untreated mental illness, drug addiction, etc. and lived in the Square prior to the occupation. A failure to elevate issues faced by the homeless residents to equal standing as other issues.

White people setting the agenda and taking leadership roles during meetings, elevating issues that negatively impact them and dismissing issues that privilege themselves while oppressing others. The failure of white people to acknowledge or realize why people from marginalized groups may feel excluded from the movement.

Positive references to “forefathers” that fail to identify them as slave owners, misogynists, etc.

Tokenizing of marginalized groups and pervasive forms of “othering”. Appropriation of culture (white people dreads, names and symbols from marginalized cultures being appropriated).

White people favoring a focus on national issues as opposed to local issues and failing to identify with local issues because DC’s issues reflect the astounding disparities that elevate white people (specifically white males) and oppress people from marginalized groups.

A white man comparing addressing the colonization of Americas to “an oppression pissing contest”.

White people acting out white privilege then denying that it exists.

During an action, people took down the DC flag -unaware of its significance to the residents of DC and their struggle for statehood.

Outreach actions to encourage DC residents to join Occupy DC rather than learning about or offering support to ongoing community struggles.

Failure to make meetings and assemblies accessible to people who are deaf and to people with disabilities.

Failing to create safe spaces by failing to adequately address oppressive, offensive, threatening behavior.

A privileging of individuals who sleep at McPherson, ignoring the myriad of obstacles that many individuals from marginalized groups face including concerns for personal safety, childcare and other family responsibilities, work obligations, etc.

Many of the residents of the DC do not speak English. Lack of language access and sensitivity at Occupy DC have made this space inaccessible and unwelcoming to many.

People whose privilege affords them relative safety in interactions with the police exposing the camp to greater police presence through aggressive acts and vandalism.

An overly U.S.-centric view that fails to acknowledge that the 1% seeks to dominate the entire world. A naïve aversion to the term “empire” places Occupy DC at odds with other Occupy sites, despite DC being the heart of the empire.

I can’t comment on any of these allegations. I wasn’t there. But whether you were nodding your head in solemn agreement or shaking it in exasperation as you went down the list, you probably didn’t find the group’s grievances or jargon unfamiliar.

Chance are that wouldn’t have been the case in 2011, unless you were already involved in radical circles. To the average Xennial or Millennial who’d registered Democrat just to vote for Obama in the 2008 primaries, at least a few of these items would have sounded a mite outlandish, if not altogether foreign. (“Cis?” “Progressive stack?” “Appropriation of culture?” “Safe spaces?”)

While the economic populist rhetoric of the 99% and 1% faded into the background, the cultural politics enunciated in the Occupy K Street Manifesto have leeched into the mainstream. After all, a large swathe of the occupiers and attentive sympathizers were college-educated, and many of them subsequently got white-collar jobs (or never left them, in some cases) and carried their values into the workplace with them. (Whether Occupy was the catalyst, an inflection point, or simply a salient increment in the shift deserves examination.)

This set of moral values—pejoratively called “wokeism”—has since been embraced by multinational corporations, NGOs, academia, public schools, city governments, the culture industry, the newsroom, and the constellation of urban professionals constituting Piketty’s “Brahmin left.” As it did in the aftermath of the 1960s, the Establishment digested those parts of the Occupy movement that could be safely (or even usefully) integrated into its existing program, and spat out the seeds.

Marx and Engels' greatest failure was underestimating the ability of elite capitalists to adapt as a means of self-preservation, which they have effectively managed for around 200 years. Slavery became morally intolerable, so it was replaced with cheap/child factory labor. But Americans grew tired of seeing broken, overworked, poisoned people in plain sight, so the most grotesque forms of exploitation were simply moved overseas and conveniently out of view.

Talk of wealth redistribution scares capitalists, so all the collective energy driving contemporary social justice movements was skillfully funneled into identity grievance politics, which are no threat to the wealthy and powerful - thus we have Bain Capital bloodsucker Mitt Romney marching with BLM, while multimillionaire Nancy Pelosi and Wall Street's favorite Senator Chuck Schumer don Kente cloths and kneel in protest.

We shouldn't be surprised that a class of cutthroat amoral entrepreneurs have proven so capable at adapting to changing circumstances. This is what Wallace was going on about in Blade Runner 2049.

So they've compromised just enough to make us feel we have a small victory? Just enough of us are 'in' that there's no leadership, not that Occupy's leadership was leading anyways? The escape valve is releasing so fast those up top are never in danger?

But people still complain and have grievances, and now we complain about "I hear you" responses from corpo as well. Hmm.